Should Pediatricians Prescribe Kindness?

An innovative program shows that pediatricians may be able to contribute

to healthy child development by encouraging kids to be kind.

When parents take their children to a pediatrician for a wellness

check, they expect to get reports on their children’s healthy development—if

they’re growing properly, eating and sleeping well, or in need of vaccines.

By

Jill Suttie

They probably don’t expect to get a prescription for kindness.

But at Senders Pediatrics, a private practice in Cleveland, Ohio, and one of the Greater Good Science Center’s 16 Parenting Initiative grantees, this is exactly what parents are getting. The clinic’s parent education coordinator, Joan Morgenstern, has developed a program to produce events, lessons, and tools promoting kindness. Based on evidence that practicing kindness and purpose benefits children, the program helps kids care for others and flourish themselves.

While the program is in its infancy, it’s a model that is popular with parents and kids, and has helped the staff at Senders Pediatrics—particularly during this difficult time of COVID. Shelly Senders, the clinic’s founding pediatrician, hopes their focus on kindness and developing the “whole child” is a model that can be replicated more widely.

“My goal in all of this is to get the American Academy of Pediatrics to endorse the concept of teaching kindness in every pediatric practice,” he says.

How and why to encourage kids to help others

There are many reasons to encourage kids to be kind. For one, it helps build positive relationships, which are important for developmental growth and success in life. More broadly, kindness is a moral virtue that can lead to more trusting, cooperative societies. And picking up kindness as a value from a young age can have positive effects later in life.

When kids are kind, they are happier and less likely to have social or behavioral problems. Kids who do nice things for others may have a greater sense of agency and purpose, too—meaning, they see that their actions can have a positive impact in the world and feel more capable of changing things for the better.

Given the benefits to mental health, it’s not too surprising that kids who practice kindness could be physically healthier, too. At least one study found that adolescents randomly assigned to volunteer had significantly better cardiovascular function than those waiting to volunteer.

To launch Senders Pediatrics’s kindness program, Morgenstern organized a Community Kindness Day in 2019 that gathered hundreds of families at a local community center. Researcher Stephen Post presented data showing that kindness improves physical and mental health, and booths were set up where kids could showcase their philanthropic work in the community and inspire other kids to get involved and find purpose by doing good.

“We really focused on our Cleveland community that had already taken initiative to get involved in community activism, social service, and serving others,” she said. “The fact that we were having kids lead was probably one of the most impactful parts of the program.”

According to Maurice Elias, a Rutgers University researcher who has been an advisor to Morgenstern and her program, the event was a success on multiple levels. It gave parents a reason to want to instill kindness in kids, legitimized the importance of social-emotional skills, and allowed kids to take charge.

“When kids engage in these kinds of public acts, it builds their skills, self-esteem, and confidence; it gives them an incentive to learn how to communicate better,” he says.

The many ways Senders Pediatrics encourages kindness

Morgenstern comes from an education background, where the virtues of encouraging children’s social and emotional growth have been understood for years. But to see this idea promoted in a pediatric clinic was novel for her.

“I thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be remarkable if doctors were spouting this message about social and emotional learning?’ Because doctors exude a sense of authority (for some people, at least), that means people will pay more attention to the message,” she says.

Her overall concept was to create opportunities for kids to acquire a habit of kindness that could be integrated into their lives, while also stressing the importance to health. After Kindness Day, she developed worksheets, activity cards, kits, monthly newsletters, and more—all aimed at promoting these important values while not stressing the busy pediatric staff.

Senders was particularly enthused about Morgenstern’s kindness cards, which had ideas for practicing kindness at nearly any age and could be handed out at well checks.

“You can start at age three, four, or five, and integrate kindness into your regular well-child care visit,” he says.

Unfortunately, some of Morgenstern’s ideas had to be jettisoned when COVID hit, including the second annual Kindness Day. But she got creative and sent out card-making materials around Valentine’s Day, encouraging kids to send valentines to people in the community who could use a boost—like first responders or elderly folks in nursing homes. In December, she asked kids to perform a good deed for someone else, providing kids with a “kindness kit” with more ideas of how to be kind.

According to Elias, these types of activities are successful because they expand a kid’s idea of how kindness matters more broadly in the world and introduce kids to the intrinsic rewards of being kind.

“Kids begin to understand that many people need kindness,” he says. “Once they start to think about these folks, and they do something kind and get a reply, that is incredibly reinforcing.”

Morgenstern wasn’t just interested in helping children, though. She also wanted to consider how parents were struggling during the pandemic. Many of them were having a hard time getting their kids to wear masks; so, Morgenstern began writing children’s books, such as one called The Task of the Mask, which made salient to kids the reasons why mask-wearing was an act of kindness.

“Something like this is of tremendous value to parents, because it deals with the issues that parents are experiencing,” says Elias. “It’s something that’s feasible that’s not going to take much time but is engaging to kids.”

Why Senders may be on to something

While it’s unclear how much Senders’s program can change the culture of a whole community, it has been well-received by parents whose kids have participated.

After attending Kindness Day, a seven-year-old patient at Senders Pediatrics, Garett, was encouraged to apply for a “B.E.E. Kind” grant the clinic designed, which paid for the creation of a “Kindness Corner” at his school. He and his mom, Shelly Hyland, purchased books on kindness, put Post-it notes in the school library where kids could leave kindness messages for each other, and created a snack cart for those who couldn’t afford school snacks.

“I was able to teach my son about writing grants to get money and materials needed to support ideas and causes that he is passionate about,” says Hyland. “He learned that he could make a difference with a simple idea even though he was only seven years old!”

Has it made a difference in her son’s life? Hyland thinks so.

“I believe focusing on kindness has allowed my child to read others’ emotions and have empathy,” she says. “His idea and execution of the Kindness Corner drew support from the school and community, all of which had a positive impact on others.”

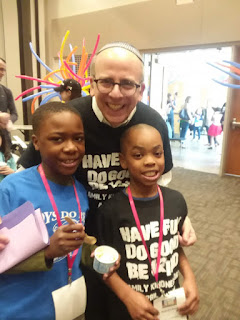

Another parent, Chrishawndra Matthews, found that her son Derrick’s interest in building literacy among boys in his community was encouraged by participating in Kindness Day, where he staffed a booth. Not only was his work honored, but he was also able to get his message across to others. “He was talking about the importance of reading and sharing with children how they can become stronger readers,” says Matthews.

Matthews was particularly happy that Senders Pediatrics drew participants from the low-income neighborhood where she and her son live, recognizing that they are the experts in how to best help their community. And, she adds, it’s important for kindness initiatives to empower people who may feel disenfranchised.

“I loved that, with the Kindness Day, it wasn’t just about suburban folks; other communities were invited, and there was diversity,” says Matthews, founder of Literacy in the Hood, which provides books for underserved communities.

These individual stories are not only heartening, but reflect how kindness can be contagious and good for all. Senders hopes that their program will be studied by researchers to validate what they are seeing anecdotally.

Matthew Lee, a Harvard researcher who coauthored a study on the physical health benefits of being a volunteer (in adults) and runs the Human Flourishing Program, is interested in doing just that. He appreciates the Senders Pediatrics approach to whole-child wellness.

“When a child goes to see the doctor, it shouldn’t just be about taking your vital signs in a narrow, biophysical sense,” he says. “Doctors should talk about how kindness relates to overall health, which includes physical well-being, sure, but also your mental well-being and your full flourishing.”

Senders believes that their kindness initiative not only helps children develop moral character, it also makes them less afraid to go to the doctor—something that makes the staff’s job easier. Before COVID hit, the clinic had a jungle gym set up in their waiting room available for kids to play on, which created a happy, welcoming environment for children. Now, they have a kindness program, which does much the same thing.

“It started out as something small, but it has become an integral part of how we operate in our office,” says Senders. “It really has changed how we practice medicine.”