Can Americans Talk About Their History Without False Antagonism?

Americans think they disagree about their national history more than they

actually do. How can we close that perception gap?

In recent years,

how Americans discuss, memorialize, and teach our nation’s history has become

a new battlefront for the culture wars in the United States.

By

Paul Oshinski

School board meetings across the nation have quarreled over classroom material, teaching practices, and mask mandates, as well as claims of ideological indoctrination. State assemblies from Missouri to North Carolina have recently proposed legislation that bans books and limits certain content.

More recently, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis threatened to ban a new College Board Advanced Placement course in African American Studies based on draft material published online. With public trust in government and other major institutions at historic lows in the country, America’s education system seems to be the latest institution to face fierce scrutiny and backlash over its functions.

As researchers at More in Common, a nonpartisan nonprofit organization that studies polarization in the U.S. and Europe, our team sought to understand how American history became the latest flashpoint of national controversy.

Over the past year, through a series of national surveys, interviews, and focus groups, we asked thousands of Americans about their views on teaching American history—and what they understood to be the views of their fellow Americans on this topic. Our findings suggest that these “history wars” are largely fought between imagined enemies. In our research, we found much of the “division” over American history and how it’s taught is driven by false perceptions of divides over fundamental aspects of the country’s past.

This is not to say real divides do not exist on how we tell our national story. While healthy debates about our history are to be had and should be encouraged, the national dialogue is often characterized by toxic levels of animosity. Though Americans have real disagreements over certain parts of our national story, inaccurate beliefs about other Americans’ views on our history—and how it should be taught—present a dangerous level of misunderstanding. Here are some ideas that might help us to better talk with each other about our history.

Perception gaps on American history

Our research process began by asking questions that aimed to measure agreement on how participants think about the country’s history and how it should be taught. Then we asked them to estimate how those in their opposing party would respond to some of these statements about history.

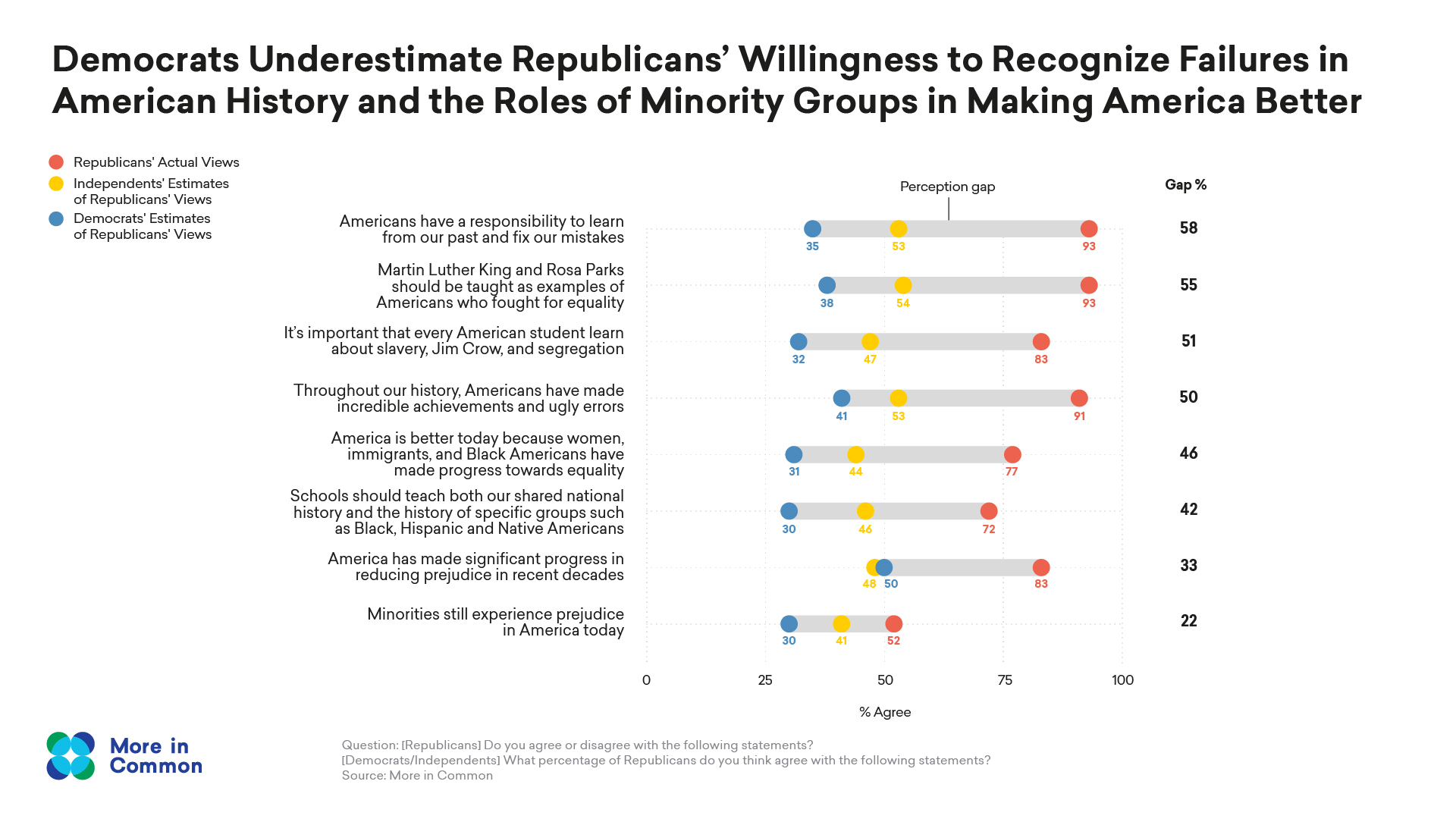

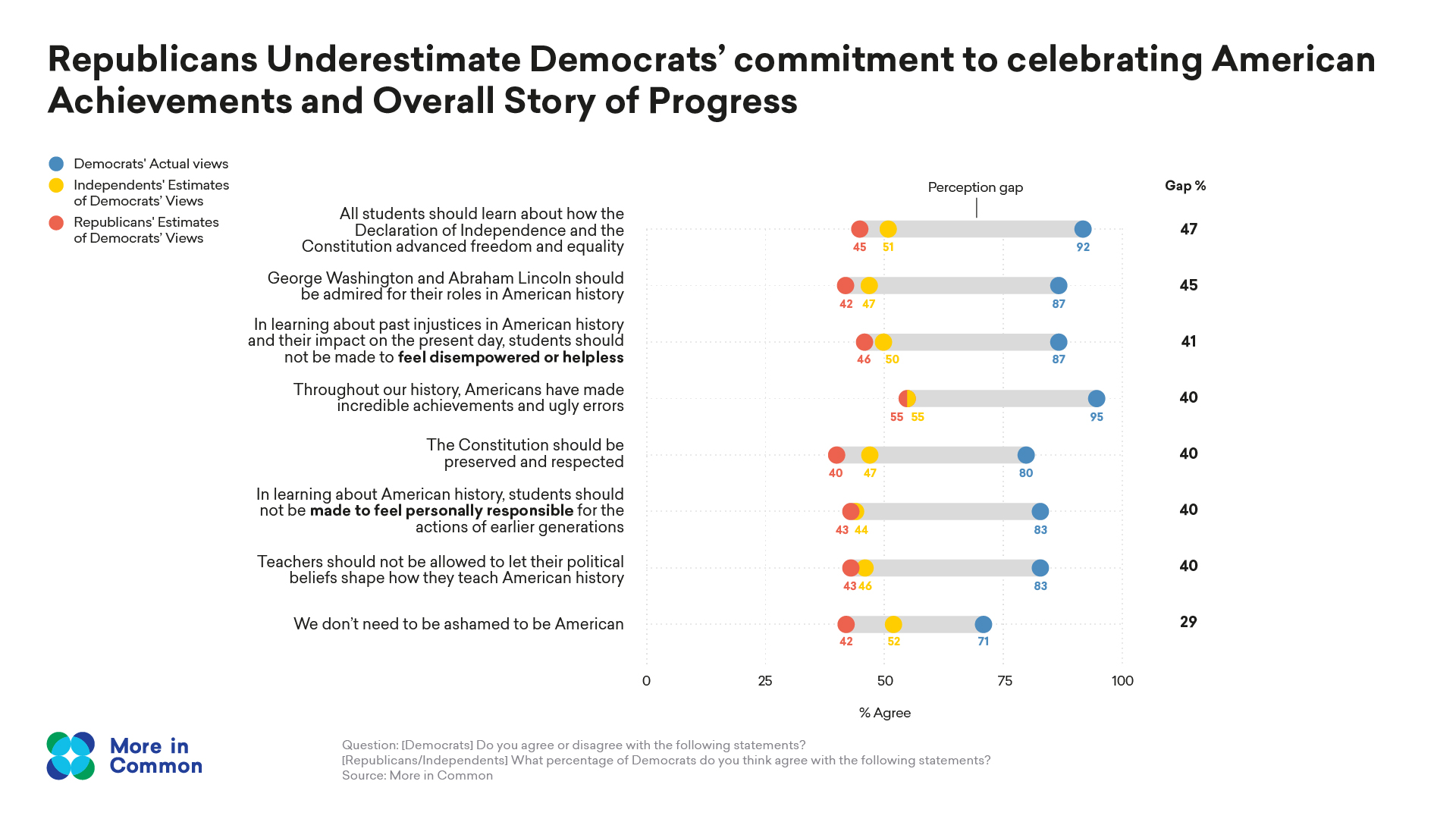

This uncovered wide gaps between what Democrats and Republicans thought the other believed about American history. We use the term “perception gap” to describe this difference between an individual’s estimate of how many of a group hold a certain view and how many actually do. On topics related to history, both Democrats and Republicans overestimated the proportion of their political opponents holding views they disagree with by nearly 50%.

In studying perception gaps around American history, we found that Republicans think Democrats want to teach a history exclusively defined by shameful oppression and guilt, while Democrats believe Republicans want to overlook grave injustices like slavery and racism—yet both impressions are incorrect.

For example, the proportion of Republicans who agree that “Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks should be taught as examples of Americans who fought for equality” is more than two times more than Democrats think (93% versus 35%). In another example, about twice as many Democrats believe “students should not be made to feel guilty or personally responsible for the errors of prior generations” than Republicans think (83% versus 43%).

Our research found that Americans agree on how to teach American history, even on issues that are perceived as highly contentious. We found that most Americans believe it is important to teach the history of racism (71%) and for students to learn about the history of Americans whose racial backgrounds differ from their own (80%). Across many areas connected to matters of race and racism, such as teaching the history of slavery, Jim Crow, and segregation, we find strong levels of support across ideological and racial lines.

What we see is a common story that resonates among most Americans. Americans of all political orientations want students to learn a history that celebrates our strengths and also probes our failures. Americans overwhelmingly agree that the experiences of underrepresented groups are an important part of that history, and they agree that if students are better informed about America’s past, there’s a better chance of not repeating past failures.

The real divides

Despite the common ground we found, our research also uncovered real divisions that exist around American history and how we teach it. Americans are divided on how much present injustices are a result of the past, and the degree of emphasis currently given to the histories of underrepresented groups. We found, however, that these divides are driven especially by Americans who are the most ideologically extreme and politically engaged.

In 2018, we published a report called “Hidden Tribes” that identified seven distinct groups of the American public based on their core beliefs. This segmentation enables us to transcend traditional surveys that rely on political affiliation, race, and other demographics and instead provide deeper insights about how core beliefs differ across society. The most ideologically extreme groups identified were Progressive Activists on the left and Devoted Conservatives on the right.

Our research on American history found that divides on this topic are often exacerbated by the most ideologically extreme, politically active Hidden Tribes groups. While significant variation exists across racial groups over whether people feel that the history of underrepresented groups is treated as more important than the history of Americans in general, the ideological extremes are in near-total opposition to each other. That is, Progressive Activists overwhelmingly disagree (94%) that our teaching of history prioritizes the stories of underrepresented groups, whereas Devoted Conservatives uniformly agree (86%).

Together, these two Hidden Tribes groups represent just 14% of the American adult population. Yet these groups are the most politically engaged Americans who are most likely to vote, post about politics on social media, and call members of Congress. In turn, schools and elected officials may mistake these more extreme Americans to be representative of the views of the average American.

One may reason that Americans are simply thinking about the most extreme partisans when they are estimating the views of the other party. However, our research found that both parties think the views of the other are much more extreme than the most extreme members in each party. Americans truly have imaginary enemies in their head when they are thinking about the views of those on the other side of the aisle.

These perception gaps obscure the reality that most Americans agree we should teach history in a way that is both celebratory and critical, inclusive of all groups, without imparting guilt or shame. Americans are more united than divided over how to teach history, yet we only see the divisions.

Steps toward reconciliation

We identified some factors that might fuel the current rift over our national story.

First, affective polarization—or negative feelings or attitudes toward members of an opposing political party—have increased substantially since the 1990s. Roughly three in four Democrats and Republicans alike view the other side as “hateful,” “brainwashed,” and “arrogant.”

These negative feelings toward partisans can prompt inaccurate perceptions of the other side on issues like American history. In addition, the education field faces distrust: Our research found that about half of Americans do not trust education officials to be politically neutral in designing curricula, and only a minority of Americans (41%) think public schools are doing their best to teach American history in an accurate and unbiased way. If most Americans do not trust educators to teach history, they might assume course content is ideological or propagandized.

Finally, our study found that most Americans (71%) feel that the country is divided on how to teach our history. “Divided” was also the word Americans were most likely to choose when asked how to describe the country today. This feeling may contribute to the belief Americans have that they do not share much common ground with those across the aisle on basic American history.

Quarrels over how and what our children should be taught are not going away. However, conversations often reach a toxic level—and they’re too often focused less on real divides and more on imagined enemies. Through our research, we identified recommendations that can help create a healthier political and educational landscape characterized by less misunderstandings, more civility, and a focus instead on substantive disagreements.

1. Learn about, acknowledge, and reduce perception gaps. These misunderstandings of the views of others on American history are not harmless, and reducing them has the potential to make important positive changes in political attitudes. If partisans were aware of how much common ground existed across party lines, they might feel fewer negative emotions toward their party counterparts. Research on perception gaps has found that correcting inaccurate views of partisans on certain topics can reduce American’s support for partisan violence, and a recent preliminary academic experiment where partisans were shown the policy overlap among their party and the opposing party yielded significant reductions in partisan animosity.

2. We all can do our best to reduce our own perception gaps. That may mean choosing a wider range of news sources to better understand differences instead of content that amplifies the views of “conflict entrepreneurs.” In addition, we can become more aware that our media feed may presume conflict on topics related to American history. Increased negative emotion in language has been found to correlate with a higher spread rate within ideological groups. Staying more attuned to how digital spaces operate can help reduce the chance of mistaking content online for the views of the average American. Additionally, research has found that encouraging internet users to think about the accuracy of claims on social media reduces the likelihood of hyper partisan content.

3. Enter into dialogue with someone with a different political viewpoint. Studies of cross-partisan dialogue have found that—under the right conditions—conversations between Americans of differing political views can reduce affective polarization. Friendships across political differences can also reduce hostility between groups, as people find commonality between themselves and another outgroup. We can all work to build better connections with those who think differently than us to gain a better understanding of the views of others.

4. Help build an alternative ecosystem. A need also exists for a larger ecosystem of local and national partners who can work across differences to find solutions that don’t seek to intentionally stoke fear. Often, organizations that work around the topic of American history do not know each other, do not talk to each other, and do not realize that their combined efforts may be more effective in driving positive change in the field, especially in response to actors who simply seek to divide. We believe increased connections and relationships among ideologically diverse organizations in the history space who share a goal to tell history accurately can work as a strong force against groups and individuals who simply seek to divide.

Conversations about American history are also often framed in extreme binaries, but our research demonstrates there is much more complexity to the views of Americans on this topic. Americans agree over most major ways to teach history, highlighting both the countries’ grave injustices and incredible achievements. Often, the most extreme voices—out of step with the views of most Americans—are the loudest in school board meetings, on social media, and in politics. Assuming more nuance in conversations about American history can help reduce misperceptions. Organizations and practitioners in politics, advocacy, civil society, education, and history can be confident that Americans hold complex views about our nation’s history.