Nerve Zap Might Ease Pain of Herniated Disk

By Alan Mozes

HealthDay Reporter

What if a simple zap to the spine could relieve the debilitating lower back and leg pain brought on by a herniated disk?

Such is the promise of "pulse radiofrequency" therapy (pRF), which sends inflammation-reducing pulses of energy to nerve roots in the spine, a new study claims.

The therapy is not new, having first received U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval in the 1980s.

But recent advances in CT scan technology now enable clinicians to deploy those energy pulses with much more accuracy, experts said. And the new research suggests the treatment could prove a boon to back pain patients for whom standard therapies have failed to do the trick.

"I was amazed with the results of pRF," said study author Dr. Alessandro Napoli. "Especially having read, as a radiologist, numerous lumbar MRI scans of patients with recurrent hernia after surgery."

And as a patient himself, Napoli added that "from personal experience I can tell you that the treatment is not painful, and the results are appreciated within days after a single treatment lasting 10 minutes."

Napoli is a professor of interventional radiology at Sapienza University of Rome in Italy.

He and his colleagues plan to report their findings Tuesday at the Radiological Society of North America annual meeting, in Chicago. Such research is considered preliminary until published in a peer-reviewed journal.

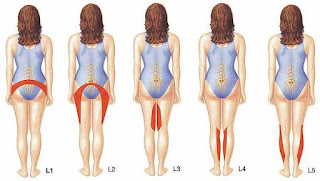

Lower disk herniation results when the insulating disks that sit between spinal vertebrae tear open, allowing jelly-like material to protrude and exert pressure on surrounding nerve roots. Beyond lower back pain, the condition often triggers sciatica, a pain that radiates down a patient's leg.

Standard therapies include over-the-counter pain meds, corticosteroid spinal injections, and/or invasive spine surgery that sometimes involves disk removal and vertebrae fusion.

The problem, said Napoli, is that such options entail risks without assured relief.

"Steroid injections are effective only in portion of the patients, and generally require more sessions," he noted. And though surgery safety has "largely improved," Napoli pointed to the risk for bleeding and infection, the need for a minimum two- to three-day hospital stay, the high cost, and the fact that some patients ultimately realize little benefit.

By contrast, pRF is scalpel-free, delivering radio signals directly to affected nerves via a CT scan-guided electrode. The process, said Napoli, requires no hospital stay, is noninvasive, far cheaper and less risky.

"The rationale for using pRF on disk herniation is that we eliminate the inflammation process of the compromised nerve root," he explained. "Without inflammation the pain fades, and the body starts a self-healing process that allows for complete resolution of the disk herniation in a large proportion of patients."

For the study, the Italian investigators compared 128 lumbar herniation patients who underwent a single 10-minute round of CT-guided pRF with 120 patients who received one to three rounds of steroid injections.

All the patients had already undergone standard interventions, with poor results.

By the one-year mark following either treatment, a full "perceived" recovery was reported by 95 percent of the pRF patients, compared with just 61 percent of the steroid injection patients.

Dr. Daniel Park, director of minimally invasive orthopedic spine surgery at William Beaumont Hospital in Royal Oak, Mich., offered some caution on the findings.

He noted that because "the majority of people with back pain improve with time and exercise alone," it remains an open question as to whether the pRF procedure really cured the condition.

Still, Park noted that diagnostic uncertainty can undermine the ability of surgery to get at the true source of a patient's pain, given that "the problem with low back pain is that there are many causes of it, and physicians have trouble identifying the cause of pain."

Nevertheless, he remains unsure if pRF is truly ready for prime time.

"Best case, I think [pRF] could be an option for people if they [have already] failed therapy and medication," said Park. "It may be a similar option for people if they do not or cannot have steroid injections, but they need more treatment. I think this is experimental, and should not be first-line."

HealthDay Reporter

What if a simple zap to the spine could relieve the debilitating lower back and leg pain brought on by a herniated disk?

Such is the promise of "pulse radiofrequency" therapy (pRF), which sends inflammation-reducing pulses of energy to nerve roots in the spine, a new study claims.

The therapy is not new, having first received U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval in the 1980s.

But recent advances in CT scan technology now enable clinicians to deploy those energy pulses with much more accuracy, experts said. And the new research suggests the treatment could prove a boon to back pain patients for whom standard therapies have failed to do the trick.

"I was amazed with the results of pRF," said study author Dr. Alessandro Napoli. "Especially having read, as a radiologist, numerous lumbar MRI scans of patients with recurrent hernia after surgery."

And as a patient himself, Napoli added that "from personal experience I can tell you that the treatment is not painful, and the results are appreciated within days after a single treatment lasting 10 minutes."

Napoli is a professor of interventional radiology at Sapienza University of Rome in Italy.

He and his colleagues plan to report their findings Tuesday at the Radiological Society of North America annual meeting, in Chicago. Such research is considered preliminary until published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Lower disk herniation results when the insulating disks that sit between spinal vertebrae tear open, allowing jelly-like material to protrude and exert pressure on surrounding nerve roots. Beyond lower back pain, the condition often triggers sciatica, a pain that radiates down a patient's leg.

Standard therapies include over-the-counter pain meds, corticosteroid spinal injections, and/or invasive spine surgery that sometimes involves disk removal and vertebrae fusion.

The problem, said Napoli, is that such options entail risks without assured relief.

"Steroid injections are effective only in portion of the patients, and generally require more sessions," he noted. And though surgery safety has "largely improved," Napoli pointed to the risk for bleeding and infection, the need for a minimum two- to three-day hospital stay, the high cost, and the fact that some patients ultimately realize little benefit.

By contrast, pRF is scalpel-free, delivering radio signals directly to affected nerves via a CT scan-guided electrode. The process, said Napoli, requires no hospital stay, is noninvasive, far cheaper and less risky.

"The rationale for using pRF on disk herniation is that we eliminate the inflammation process of the compromised nerve root," he explained. "Without inflammation the pain fades, and the body starts a self-healing process that allows for complete resolution of the disk herniation in a large proportion of patients."

For the study, the Italian investigators compared 128 lumbar herniation patients who underwent a single 10-minute round of CT-guided pRF with 120 patients who received one to three rounds of steroid injections.

All the patients had already undergone standard interventions, with poor results.

By the one-year mark following either treatment, a full "perceived" recovery was reported by 95 percent of the pRF patients, compared with just 61 percent of the steroid injection patients.

Dr. Daniel Park, director of minimally invasive orthopedic spine surgery at William Beaumont Hospital in Royal Oak, Mich., offered some caution on the findings.

He noted that because "the majority of people with back pain improve with time and exercise alone," it remains an open question as to whether the pRF procedure really cured the condition.

Still, Park noted that diagnostic uncertainty can undermine the ability of surgery to get at the true source of a patient's pain, given that "the problem with low back pain is that there are many causes of it, and physicians have trouble identifying the cause of pain."

Nevertheless, he remains unsure if pRF is truly ready for prime time.

"Best case, I think [pRF] could be an option for people if they [have already] failed therapy and medication," said Park. "It may be a similar option for people if they do not or cannot have steroid injections, but they need more treatment. I think this is experimental, and should not be first-line."