Should You Ask Your Children to Apologize?

By Craig Smith

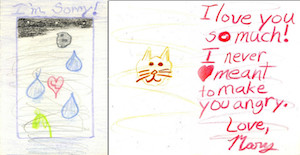

When kids say sorry, are they learning a lesson or just parroting empty words?

Have you ever felt deserving of an apology and been upset when you didn’t get one? Have you ever found it hard to deliver the words, I’m sorry?

When kids say sorry, are they learning a lesson or just parroting empty words?

Have you ever felt deserving of an apology and been upset when you didn’t get one? Have you ever found it hard to deliver the words, I’m sorry?

Such experiences show how much apologies matter. The importance placed on apologies is shared by many cultures. Diverse cultures even share a great deal in common when it comes to how apologies are communicated.

When adults feel wronged, apologies have been shown to help in a variety of ways: Apologies can reduce retaliation; they can bring about forgiveness and empathy for wrongdoers; and they can aid in the repair of broken trust. Further, sincere apologies have the physiological effect of lowering blood pressure more quickly, especially among those who are prone to hold on to anger.

How do children view and experience apologies? And what do parents think about when to prompt their young ones to apologize?

How children understand apologies

Research shows that children as young as age four grasp the emotional implications of apology. They understand, for example, that an apology can improve the feelings of someone who’s been upset. Preschoolers also judge apologizing wrongdoers to be more likable, and more desirable as partners for interaction and cooperation.

Recent studies have tested the actual impact of apologies on children. In one such study, a group of four to seven year olds received an apology from a child who failed to share, while another group did not get an apology. The participants who received the apology felt better and viewed the offending child as nicer as well as more remorseful.

Another study exposed children to a more distressing event: A person knocked over a tower that six to seven year olds were building. Some children got an apology; some did not. In this case, a spontaneous apology did not improve children’s upset feelings. However, the apology still had an impact. Children who got an apology were willing to share more of their attractive stickers with the person who knocked over the tower compared to those who did not get an apology.

This finding suggests that an apology led to forgiveness in children, even if sadness about the incident understandably lingered. Notably, children did feel better when the other person offered to help rebuild their toppled towers. In other words, for children, both remorseful words and restorative actions make a difference.

When does a child’s apology matter to parents?

Although apologies carry meaning for children, views on whether parents should ask their children to apologize vary. A recent caution against apology prompting was based on the mistaken notion that young children have limited social understanding. In fact, young children understand a great deal about others’ viewpoints.

When and why parents prompt their children to apologize has not been systematically studied. In order to gain better insight into this question, I recently conducted a study with my colleagues Jee Young Noh and Michael Rizzo at the University of Maryland and Paul Harris at Harvard University.

We surveyed 483 parents of three- to 10-year-old children. Most participants were mothers, but there was a sizable group of fathers as well. Parents were recruited via online parenting discussion groups and came from communities all around the U.S. The discussion groups had a variety of orientations toward parenting.

In order to account for the possibility that parents might want to show themselves in the best light, we took a measure of “social desirability bias” from each parent. The results reported here emerged after we statistically corrected for the influence of this bias.

We asked parents to imagine their children committing what they would consider to be “transgressions.” We then asked them how likely they would be to prompt an apology in each scenario. We also asked parents to rate how important they felt it was for their children to learn to apologize in a variety of situations. Finally, we asked the parents about their general approaches to parenting.

The large majority of parents (96 percent) felt that it was important for their children to learn to apologize following an incident in which children upset another person on purpose. Further, 88 percent felt it was important for their children to learn to apologize in the aftermath of upsetting someone by mistake.

Fewer than five percent of the parents surveyed endorsed the view that apologies are empty words. However, parents were sensitive to context.

Parents reported being especially likely to prompt apologies following their children’s intentional and accidental “moral transgressions.” Moral transgressions involve issues of welfare, justice, and rights, such as stealing from or hurting another person.

Parents viewed apologies as relatively less important following their children’s transgressions of social convention (e.g., breaking a rule in a game, interrupting a conversation).

Apology as a way to mend rifts

It’s noteworthy that parents were very likely to anticipate prompting apologies following incidents in which their children upset others on purpose and by mistake.

This suggests that a focus for many parents, when prompting apologies, is addressing the outcomes of their children’s social missteps. Our data suggest that parents use apology prompts to teach their children how to manage difficult social situations, regardless of underlying intentions.

For example, 88 percent of parents indicated that they would typically prompt an apology if their child broke a peer’s toy by mistake (in the event that the child did not apologize spontaneously).

Indeed, parents especially anticipated prompting apologies following accidental mishaps that involved their children’s peers (and not parents themselves as the wronged parties). When a child’s peer is a victim, parents likely recognize that apologies can quickly mend potential interpersonal rifts that may otherwise linger.

We also asked parents why they viewed apology prompts as important for their children. In the case of moral transgressions, parents saw these prompts as tools for helping children take responsibility. In addition, they used apology prompts for promoting empathy, teaching about harm, helping others feel better, and clearing up confusing situations.

However, not all parents viewed the importance of apology prompting in the same way. There was a subset of parents who were relatively permissive: warm and caring but not overly inclined to provide discipline or expect mature behavior from their children.

Most of these parents were not wholly dismissive of the importance of apologies, but they consistently indicated being less likely to provide prompting to their children, compared to the other parents in the study.

When to prompt an apology

Overall, most parents in our study viewed apologies as important in the lives of children. And the child development research described above indicates that many children share this view.

But are there more and less effective ways to prompt a child to apologize? I argue that parents should consider whether a child will offer a prompted apology willingly and sincerely. A recently completed study sheds some light on why.

In this study—currently under review—we asked four- to nine-year-old children to evaluate two types of apologies that were prompted by an adult. One apology was willingly given to the victim after the apology prompt; the other apology was given only after additional adult coercion (“You need to say you’re sorry!”).

We found that 90 percent of the children viewed the recipient of the prompted, “willingly given” apology as feeling better. However, only 22 percent of the children connected a coerced apology to improved feelings in the victim.

So, as parents ponder the merits of prompting apologies from children, it seems important to refrain from pushing one’s child to apologize when he or she is not ready, or is simply not remorseful. Most young children don’t view coerced apologies as effective.

In such cases, interventions aimed at calming down, increasing empathy, and making amends may be more constructive than pushing a resistant child to deliver an apology. And, of course, components like making amends can accompany willingly given apologies as well.

Finally, to arguments that apologies are merely empty words that young children parrot, it’s worth noting that we have many rituals that involve rather scripted verbal exchanges, such as when two people in love say “I do” at a wedding or commitment ceremony.

Just as these scripted words carry deep cultural and personal meaning, so too can other culturally valued verbal scripts, such the words in an apology. Thoughtfully teaching young children about apologizing is one aspect of teaching them how to be caring and well-regarded members of their communities.