Gifts for Gifted Children

--by Betsy Cornwell

Alfred Eisenstaedt, Children at a Puppet Theatre, Paris, 1963

Each summer I teach creative writing classes at the Johns Hopkins Center for Talented Youth. It’s a wonderful job for many reasons: my colleagues are uniformly, eccentrically brilliant, I’ve taught at campuses all over the country, from Los Angeles to the U.S. Virgin Islands, and since the program is a sleepaway camp, the mood is always more summer vacation than school-day drudgery.

But the real reason I love this job, what makes me cross an ocean and leave my spouse behind for six weeks every year, is my students: my breathtakingly intelligent students, radiating curiosity and teenage awkwardness and desperation to learn. These are kids who scored much higher on the SAT than the average college applicant . . . when they were twelve. They have triumphed in many rounds of talent searches, they take classes at the local university after they get out of middle school for the day, and they can best most adults in academic debates. Their genius incandesces.

I am sure you’ve met a child just like them. Maybe you knew one in school. Maybe you’re raising one.

Or maybe, like me, you used to be one.

I am writing to you, to those of you who know highly intelligent children. Much is made of trying to help these kids “achieve their potential,” in all the myriad ways that can mean. It is so tempting to urge a gifted child to use all of their gifts right now, right away. We believe we’re helping them to be their best selves.

Illustration “Ein Märchen” The Fairy Tale, Artist unknown, circa 1900.

Yet I love Parabola because this magazine offers an alternative to the constant buzzing race toward achievement, the breathless pressure that so many of us feel to keep going, keep achieving, keep doing, and then to feel ashamed when we can’t compete anymore. No. Much of the writing here shows the wisdom of stillness, of quiet, of peace. Of rejection of the ego, the urge toward personal achievement above all else.

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve praised someone’s child to the heavens—how thoughtful and incisive their in-class comments are, the beauty and clarity of their writing, how kind and encouraging they are toward their fellow students, how utterly they have succeeded in a very challenging course—only to have the parent say, “What else should we have them do?”

I see so many parents who automatically leap to asking more of children who are already giving so much of themselves, already performing at so high a level that they can take college-level courses at thirteen. Academic achievement comes easily to many of these children, but the pressure they feel to keep achieving does not. It’s a lot for a child to handle, even a gifted one. Maybe especially for them. For the most part they’re gentle, thoughtful kids who are loath to question their parents’ wishes. I see them edge close to breakdown, to oblivion, all by striving to do and be what we ask of them.

The vast majority of their parents mean well; they want to help their children get into good colleges and secure comfortable futures. Many of them also want to take pride in their children’s achievements, of course, but I don’t think it would be fair to imply that this is their primary motivation. They want to do right by their kids. For many parents, that means pushing as hard as they can.

But as a teacher of gifted children, and as a survivor of that label myself, I am writing to ask that we stop. To suggest that space and gentleness and lack of pressure is exactly what these children need.

What gifts can we offer gifted children? How can we who are their guardians do justice by them?

The first gift is not to praise them for their talents alone. Just as a beautiful child is often praised only for their beauty, and grows simultaneously vain and insecure, an intelligent child can easily learn that their mind is what makes them loveable. Praise can morph into expectations that feel exhausting, or even impossible, to meet. It can lead to panic attacks about a B on a test, a myopic focus on school, and disproportionate feelings of failure when they do any work that falls short of perfection. They learn that if they can’t do something easily and well, can’t elicit praise at the first attempt, that it isn’t worth doing at all. They grow terribly fearful of failure, and even of risk. I and many other ex-talented-youths know this all too well.

Instead, give these children the gift of praise for attributes that have nothing to do with intelligence. Praise their kindness, their empathy, their bravery and strength. Praise their hearts and souls; but don’t do so by calling them exceptional. Declare that you are glad there are people like them in the world, and by your praise help them feel they belong here. Tell them they do belong, just as they are, not that they stand out. This is the balm for a lonely child’s heart.

It also leads me to the second gift, which is ordinariness. Too many parents want their children to be exceptional, sometimes for the child’s sake, sometimes for their own. But there is a creeping insidiousness to the idea that only an extraordinary life is worth living, and that bowing out of the highest possible echelons of achievement is weakness. That it is somehow a sin not to ‘reach our potential.’

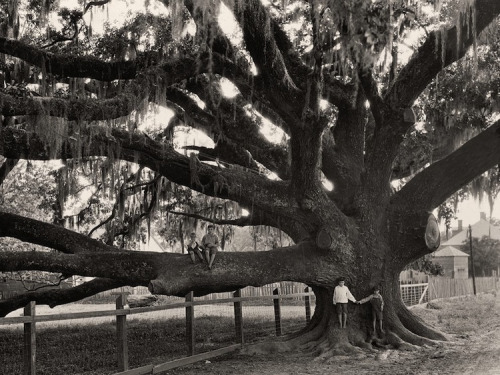

Edwin Wisherd, Children on an Oak Tree near St. Francisville, Louisiana, 1930.

Yet most of us, in the end, live ordinary lives; we are not Nobel Prize winners or leaders of nations, even if perhaps we might have been. When I think of the things that have brought the most goodness, the most spiritual health to my life, they are utterly ordinary. A kind word, a walk outdoors, the communion of human touch. Life’s greatest gifts are offered to everyone. Let your child find what makes them remarkable if they so choose; but let them be ordinary, too. They do not need to use all their gifts right now.

The third gift, then, is time. So many young people are over-scheduled, drowning in school and sports and clubs and church and jobs and volunteer work. So many of our children don’t get enough sleep, let alone time to themselves. We are teaching them to pace their lives at the same breakneck speed that leaves us tired and burnt out for our whole adulthoods. Is it not enough that we exhaust ourselves this way, but we must do it to our children, too? Is this really how we want to teach them that life should be? Give them time to breathe, time without the burden of expectation; and then, perhaps, give yourself that gift, too.

That word expectation is at the heart of what I am trying to say. If we truly want to help our gifted children, to give them gifts that will serve them well, we must divorce expectation from opportunity. All children’s needs are different, and I genuinely believe that all children are gifted. They absolutely deserve the opportunity to use their gifts, and it is therefore our responsibility to create those opportunities.

But we must not dictate what they will do with them. Children will always use their gifts in ways that their parents cannot understand, or perhaps even sanction. We must create the space in which our children can grow, and then—painfully, wistfully—step back and let them do it.

I have recently been revising my syllabus for the coming summer. Under the Class Goals heading, I describe the major assignments students will complete, and the skills I hope they will gain. In truth, though, my goals are simple: opportunity without expectation, or with as open and wide-ranging expectations as a particular course can allow. My students come to my class so often worn down, harried, and isolated. They are so worried about doing things properly that creative expression can feel like a frightening foreign language to them.

But there is no right way to tell a story, especially if it’s your own. The freedom of never being right is terrifying to them at first, but they’re young enough to leap into it with abandon after a day or two. I often wish that more adults could do the same.

That courage to leap is the fourth gift. I believe it is one of the best that we can give to any child. Encouragement is not about pushing or shaping or expectations. It has the word courage at its heart. If we can encourage our children, if we can fill them with courage, we will have done right by them.

The fifth and last gift is community, in the sense of communion. I attended CTY as a student for four years, and I am only making the tiniest rhetorical leap when I say that it saved my life. The three weeks I spent at “nerd camp” each summer were my first home, the first place where I felt truly accepted and, more than that, understood. I came from a difficult home life and a large amount of social anxiety at school, but that first summer, I met dozens of others just like me. I giggled with friends, danced with abandon to the Violent Femmes and REM, and had my first kiss. Among the weird kids, I got to be normal. It was an incredible gift.

Not every gifted child is socially awkward, a poor athlete, or any of the other concepts we might associate with them. Nearly all, however, feel some degree of loneliness and isolation—even the popular, athletic ones. There is some part of themselves that they cannot share with their peers: the part that wants to talk about the finer points of particle physics, for instance, or that just blew through the collected works of Jane Austen in a week. They’ve learned to silence it, because no one understands, or because it will make teachers and parents expect even more of them than they already give.

That’s what makes a gifted child lonely: the part of themselves they can’t share with peers or even the most well-meaning parents. Only a fellow teen genius burns with the same all-consuming excitement that they do.

As a teacher of these students, I often feel that the most I can do is give them space, and perhaps a spark—a writing exercise, a page of prose—step back, and wait for the explosion. They light each other up far more than I can.

I am a good teacher, and I am proud of the contributions I make to the program that was so vital to me as a teenager. But I know that the actual classes, as exciting and stimulating as they are, are not the point of CTY. The point is the children themselves, the community they make for each other, the life-saving understanding that they, and only they, can offer one another. As adults we have the resources to create the space for this to happen, but it does not belong to us. It never does. It is the gift they give each other.

Witnessing that gift has been one of the greatest privileges of my life. At the first weekend’s camp dance, students who’ve known each other for only a few days join hands, embrace, and sway in circles to Queen’s “Somebody to Love.” The students laugh or smile or cry with relief; chaperones quietly do the same. There is a potency of belonging in the room so thick you could float on it. Many of these students have never attended a school dance before, or have been rejected or mocked if they did. But here, in a place where their parents have sent them to improve their minds, they find instead a fellowship of the heart.

Each summer I teach creative writing classes at the Johns Hopkins Center for Talented Youth. It’s a wonderful job for many reasons: my colleagues are uniformly, eccentrically brilliant, I’ve taught at campuses all over the country, from Los Angeles to the U.S. Virgin Islands, and since the program is a sleepaway camp, the mood is always more summer vacation than school-day drudgery.

But the real reason I love this job, what makes me cross an ocean and leave my spouse behind for six weeks every year, is my students: my breathtakingly intelligent students, radiating curiosity and teenage awkwardness and desperation to learn. These are kids who scored much higher on the SAT than the average college applicant . . . when they were twelve. They have triumphed in many rounds of talent searches, they take classes at the local university after they get out of middle school for the day, and they can best most adults in academic debates. Their genius incandesces.

I am sure you’ve met a child just like them. Maybe you knew one in school. Maybe you’re raising one.

Or maybe, like me, you used to be one.

I am writing to you, to those of you who know highly intelligent children. Much is made of trying to help these kids “achieve their potential,” in all the myriad ways that can mean. It is so tempting to urge a gifted child to use all of their gifts right now, right away. We believe we’re helping them to be their best selves.

Illustration “Ein Märchen” The Fairy Tale, Artist unknown, circa 1900.

Yet I love Parabola because this magazine offers an alternative to the constant buzzing race toward achievement, the breathless pressure that so many of us feel to keep going, keep achieving, keep doing, and then to feel ashamed when we can’t compete anymore. No. Much of the writing here shows the wisdom of stillness, of quiet, of peace. Of rejection of the ego, the urge toward personal achievement above all else.

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve praised someone’s child to the heavens—how thoughtful and incisive their in-class comments are, the beauty and clarity of their writing, how kind and encouraging they are toward their fellow students, how utterly they have succeeded in a very challenging course—only to have the parent say, “What else should we have them do?”

I see so many parents who automatically leap to asking more of children who are already giving so much of themselves, already performing at so high a level that they can take college-level courses at thirteen. Academic achievement comes easily to many of these children, but the pressure they feel to keep achieving does not. It’s a lot for a child to handle, even a gifted one. Maybe especially for them. For the most part they’re gentle, thoughtful kids who are loath to question their parents’ wishes. I see them edge close to breakdown, to oblivion, all by striving to do and be what we ask of them.

The vast majority of their parents mean well; they want to help their children get into good colleges and secure comfortable futures. Many of them also want to take pride in their children’s achievements, of course, but I don’t think it would be fair to imply that this is their primary motivation. They want to do right by their kids. For many parents, that means pushing as hard as they can.

But as a teacher of gifted children, and as a survivor of that label myself, I am writing to ask that we stop. To suggest that space and gentleness and lack of pressure is exactly what these children need.

What gifts can we offer gifted children? How can we who are their guardians do justice by them?

The first gift is not to praise them for their talents alone. Just as a beautiful child is often praised only for their beauty, and grows simultaneously vain and insecure, an intelligent child can easily learn that their mind is what makes them loveable. Praise can morph into expectations that feel exhausting, or even impossible, to meet. It can lead to panic attacks about a B on a test, a myopic focus on school, and disproportionate feelings of failure when they do any work that falls short of perfection. They learn that if they can’t do something easily and well, can’t elicit praise at the first attempt, that it isn’t worth doing at all. They grow terribly fearful of failure, and even of risk. I and many other ex-talented-youths know this all too well.

Instead, give these children the gift of praise for attributes that have nothing to do with intelligence. Praise their kindness, their empathy, their bravery and strength. Praise their hearts and souls; but don’t do so by calling them exceptional. Declare that you are glad there are people like them in the world, and by your praise help them feel they belong here. Tell them they do belong, just as they are, not that they stand out. This is the balm for a lonely child’s heart.

It also leads me to the second gift, which is ordinariness. Too many parents want their children to be exceptional, sometimes for the child’s sake, sometimes for their own. But there is a creeping insidiousness to the idea that only an extraordinary life is worth living, and that bowing out of the highest possible echelons of achievement is weakness. That it is somehow a sin not to ‘reach our potential.’

Edwin Wisherd, Children on an Oak Tree near St. Francisville, Louisiana, 1930.

Yet most of us, in the end, live ordinary lives; we are not Nobel Prize winners or leaders of nations, even if perhaps we might have been. When I think of the things that have brought the most goodness, the most spiritual health to my life, they are utterly ordinary. A kind word, a walk outdoors, the communion of human touch. Life’s greatest gifts are offered to everyone. Let your child find what makes them remarkable if they so choose; but let them be ordinary, too. They do not need to use all their gifts right now.

The third gift, then, is time. So many young people are over-scheduled, drowning in school and sports and clubs and church and jobs and volunteer work. So many of our children don’t get enough sleep, let alone time to themselves. We are teaching them to pace their lives at the same breakneck speed that leaves us tired and burnt out for our whole adulthoods. Is it not enough that we exhaust ourselves this way, but we must do it to our children, too? Is this really how we want to teach them that life should be? Give them time to breathe, time without the burden of expectation; and then, perhaps, give yourself that gift, too.

That word expectation is at the heart of what I am trying to say. If we truly want to help our gifted children, to give them gifts that will serve them well, we must divorce expectation from opportunity. All children’s needs are different, and I genuinely believe that all children are gifted. They absolutely deserve the opportunity to use their gifts, and it is therefore our responsibility to create those opportunities.

But we must not dictate what they will do with them. Children will always use their gifts in ways that their parents cannot understand, or perhaps even sanction. We must create the space in which our children can grow, and then—painfully, wistfully—step back and let them do it.

I have recently been revising my syllabus for the coming summer. Under the Class Goals heading, I describe the major assignments students will complete, and the skills I hope they will gain. In truth, though, my goals are simple: opportunity without expectation, or with as open and wide-ranging expectations as a particular course can allow. My students come to my class so often worn down, harried, and isolated. They are so worried about doing things properly that creative expression can feel like a frightening foreign language to them.

But there is no right way to tell a story, especially if it’s your own. The freedom of never being right is terrifying to them at first, but they’re young enough to leap into it with abandon after a day or two. I often wish that more adults could do the same.

That courage to leap is the fourth gift. I believe it is one of the best that we can give to any child. Encouragement is not about pushing or shaping or expectations. It has the word courage at its heart. If we can encourage our children, if we can fill them with courage, we will have done right by them.

The fifth and last gift is community, in the sense of communion. I attended CTY as a student for four years, and I am only making the tiniest rhetorical leap when I say that it saved my life. The three weeks I spent at “nerd camp” each summer were my first home, the first place where I felt truly accepted and, more than that, understood. I came from a difficult home life and a large amount of social anxiety at school, but that first summer, I met dozens of others just like me. I giggled with friends, danced with abandon to the Violent Femmes and REM, and had my first kiss. Among the weird kids, I got to be normal. It was an incredible gift.

Not every gifted child is socially awkward, a poor athlete, or any of the other concepts we might associate with them. Nearly all, however, feel some degree of loneliness and isolation—even the popular, athletic ones. There is some part of themselves that they cannot share with their peers: the part that wants to talk about the finer points of particle physics, for instance, or that just blew through the collected works of Jane Austen in a week. They’ve learned to silence it, because no one understands, or because it will make teachers and parents expect even more of them than they already give.

That’s what makes a gifted child lonely: the part of themselves they can’t share with peers or even the most well-meaning parents. Only a fellow teen genius burns with the same all-consuming excitement that they do.

As a teacher of these students, I often feel that the most I can do is give them space, and perhaps a spark—a writing exercise, a page of prose—step back, and wait for the explosion. They light each other up far more than I can.

I am a good teacher, and I am proud of the contributions I make to the program that was so vital to me as a teenager. But I know that the actual classes, as exciting and stimulating as they are, are not the point of CTY. The point is the children themselves, the community they make for each other, the life-saving understanding that they, and only they, can offer one another. As adults we have the resources to create the space for this to happen, but it does not belong to us. It never does. It is the gift they give each other.

Witnessing that gift has been one of the greatest privileges of my life. At the first weekend’s camp dance, students who’ve known each other for only a few days join hands, embrace, and sway in circles to Queen’s “Somebody to Love.” The students laugh or smile or cry with relief; chaperones quietly do the same. There is a potency of belonging in the room so thick you could float on it. Many of these students have never attended a school dance before, or have been rejected or mocked if they did. But here, in a place where their parents have sent them to improve their minds, they find instead a fellowship of the heart.