Our Tenuous Boundaries: A Life in 10 Sea Creatures

"When Sabrina Imbler was in college, they enrolled in a class they thought was about whales, but which turned out to be about whaling. In one of 10 brilliant essays in their new book, Imbler recalls the class, which focused on "the systematic hunting and harvesting of the animals that brought human populations to the verge of unimaginable prosperity and whale populations to the brink of extinction." In contemplating the autopsy of the whale as a metaphor for analyzing the death of a relationship, Imbler was reminded of "all the ways we shoehorn distinctions between ourselves and other animals, often harming both of us."

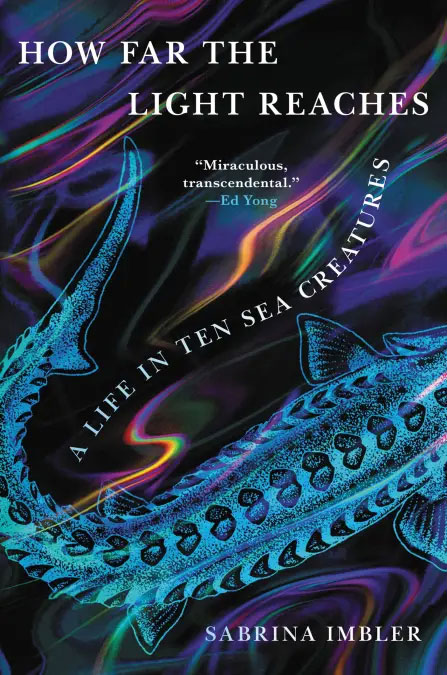

Their new book, "How Far the Light Reaches: A Life in Ten Sea Creatures," profiles often overlooked forms of aquatic life, while deftly exploring questions of identity, community, and care.

by Ashia Ajani

As if to answer those curiosities, the collection, How Far the Light Reaches: A Life in Ten Sea Creatures, proceeds to dive into distinctions, harms, and numerous other questions of being.

Imbler is a former New York Times Reporting Fellow, a science writer, and poet with a brilliant imagination and keen eye for detail, a skill set evident in this collection’s illuminating lyricism. Each chapter navigates the tenuous boundary between the human and nonhuman, profiling creatures often overlooked by us land-dwelling folks: the Chinese sturgeon, the cuttlefish, the butterflyfish. Throughout the book, Imbler weaves through topics of queerness, adaptation, family, and community, shining a critical light on the burden and beauty of survival in hostile environments and teaching us something along the way.

In the first essay, the reader is enveloped in an endearing story of a young Imbler, not yet coming to terms with their own queer autonomy, yet still able to follow their moral compass. At 13, in their local Petco, Imbler warned potential pet owners about the many illnesses and ailments that domesticated goldfish face, even though Imbler was eventually asked to leave the store. Imbler moves from this recollection to lead the reader further into the lives of sea creatures and an inextricable connection to them. “What does it mean to survive in the wild? You can’t do it without going wild yourself.” Connection is nestled alongside other desires: for wildness, for freedom, for a means to lean further into the beauty of self-creation and affirmation.

How Far the Light Reaches reveals parallels between marine animals and humans. Imbler is both observer and participant, expertly moving between narration and recollection. Tasked with revealing many shortsighted attempts to analyze sea creatures, How Far the Light Reaches creatively approaches science as a form of memory-keeping. Who gets to name a creature, and what is the power in naming? Whose memories of these creatures will paint our perspectives of them? And how are we going to deal with the environmental and social ramifications of our inability to see beyond our own human ways of navigating the world?

At the crux of each essay are ever-evolving questions. And though they lack clear answers, they are nevertheless necessary for better understanding our relationship with the natural world and ourselves. Imbler highlights the modes of survival that are some of the most radical ways of living: the use of stealth, camouflage and, occasionally, long gelatinous chain links to navigate the dangers of the deep. “Reading a creature through its camouflage seems a misguided attempt to understand its true nature, its whole self,” Imbler concludes.

Imbler’s essays exemplify the future of science and marine biology writing. As a mixed-race, queer writer, Imbler interrogates the boundaries of human/non-human relationality in conversation with our own categorizations of race and gender. “Imagine,” they write, “having the power to become resilient to all that is hostile to us.”

Imbler seamlessly moves through science journalism and personal narrative, weaving in scientists, poets, anthropologists, and naturalists. Through the lens of marine animals, Imbler dissects and identifies the many ways in which humans become complicit in our own limitations, and, perhaps more importantly, how those limitations are foisted onto others, human and non-human alike. Imbler shows us human social patterns reflected in nature, along with our impact. It is a sobering mirror: “We swarm because we are full of the joy of being together, full of anger at the systems that exclude or endanger us, full of hope for the possibilities of the future.” Such writing allows us to trace our own evolution, a reminder that we need not remain stagnant, but must instead remain open-minded, curious, and far reaching.