IntraConnected: Discovering MWe (Me + We)

"We may have a mental understanding that all of life is one inseparable whole, yet how do we actually feel into this reality? And how do we relate to others and the world from this felt awareness? Dr. Daniel J. Siegel is a visionary creative thinker, professor, and founder of the field of interpersonal neurobiology.

In this podcast transcript, Tami Simon speaks with Dr. Siegel about his book IntraConnected: MWe (Me + We) as the Integration of Self, Identity, and Belonging. They explore the direct experience of being the whole of life; interconnection versus intraconnection; honoring the inner, the inter, and the intra; E. O. Wilson's concept of consilience; the promotion of linkages as the basis of well-being; quantum physics and the study of energy; the Wheel of Awareness practice; the three-pillar practice of focused attention, opening awareness, and building kind intention; the power of wandering and relaxing the flimsy fantasy of certainty; our survival instincts and the investment in being separate; how mindfulness practice interrupts the anticipatory brain and brings us back to presence; the multiple pandemics of our time, and the lie that our identity is only in the solo self; how the tapestry of reality is of love and connection; seeing yourself as a verb instead of a noun; pervasive leadership, and how were all called to assist in the Great Turning; and more."

Tami Simon: In this episode of Insights at the Edge, my guest is Dan Siegel. Dan is a friend to me, to Sounds True, and quite honestly, he has the qualities of what I would call a universal friend. He leads with openness, curiosity, and an interest in connecting. Dan is a hugely accomplished person. He’s a graduate of Harvard Medical School and clinical professor of psychiatry at the UCLA School of Medicine. He’s the executive director of the Mindsight Institute and founding codirector of the Mindful Awareness Research Center at UCLA. Dan is someone who I would describe as a visionary creative thinker. He’s able to see commonalities in the meeting ground between different disciplines of inquiry. It was in the early 1990s that he developed the field of interpersonal neurobiology.

He’s also the author of numerous books including The Mindful Brain, The Developing Mind, and a new book that’s the subject of our conversation, IntraConnected: MWe (Me + We) as the Integration of Self, Identity, and Belonging. Additionally, with Sounds True, Dan Siegel has created an audio series called The Neurobiology of We, along with several other audio programs that you can learn more about at soundstrue.com. Now, here’s my conversation MWe-to-MWe with Dan Siegel. Dan, welcome.

Dan Siegel: Tami, it’s great to be here with you and it’s wonderful to connect in this setting, even though we have our connections in other ways. It’s a beautiful thing. Thank you for having me.

TS: Let’s start with another term that came to you. It’s original to you, IntraConnected, the title of your new book. Why did you feel the need to introduce? Tell us the origin story, if you will, of this word, intraconnected.

DS: Yes, well, thanks for starting with that, Tami. The number of words we have is huge, so to make a new word is always a big deal because we probably talk too much anyway. We should more be in the experience of being and not filtering everything through language. Back in your home state, in Colorado, I was with some system scientists doing a retreat where we were up in the mountains, in Crestone, in a place actually where people have been meditating, the evidence suggests, for about 20,000 years. In that experience, we were placed within the forest by our individual selves for three days. When we came out, we met in a circle in the forest and everyone was sharing what that experience for those three days was like. My colleagues said some incredibly beautiful things. They felt interconnected with the whole forest. They felt interdependent, interwoven.

They used Thich Nhat Hanh’s beautiful term interbeing. They felt they were interwere. All these inter- terms were being used and then it came my time to speak in the circle. And I really resonated with the feeling that everyone was describing, but the word beginning with inter- just didn’t feel right because the experience for this body, of Dan in that forest, was that after a few hours, the separation of this encapsulated system called a body and the trees and the creek and the sky dissolved away. And there was a kind of wholeness to it. So I was the clouds, I was the creek, I was the trees, I was the body. So, when I was trying to explain this to my colleagues, I said, I don’t even know what to say in English, that there was a connection of the whole that was… And there was no word. So I said, “Oh, I know what the word is, it’s intraconnected.” There was a connectedness within the whole of that fullness of being.

Everyone sort of nodded and said, “Yes, interconnected, great, whatever.” Then, when we went back to our place we were staying and I had a computer and I wanted to take some notes about what that three-day experience was like, every time I would type, “Well, it was intraconnected,” the word corrector, whatever it’s called, the autocorrector would change it to interconnected. I thought there was a defect in my computer, so I looked it up. There is no word for the connections within the whole, there is no word intraconnected. So then, I felt if in English, at least, we don’t have a word that speaks to the connectivity within the whole, how do we actually talk about that or act on behalf of this greater good? So that is how the word was born.

I’m surprised it isn’t a word, actually. The more I use it, the more I see how useful it is to talk about being the whole of life, for example. How do we speak on behalf of that? How do we feel into that? How do we act on behalf of the benefit for the whole? So that’s where the word comes from.

TS: No, I think some of these distinctions, they’re nuanced and yet, they have a lot of meaning. So if you were to say right now you and I, we’re interconnected, I feel that.

DS: Yes.

TS: If you were to say we’re intraconnected, what would be the distinctions? What would you be meaning by the interconnected versus the intraconnected?

DS: Yes.

TS: If you were talking about you and me right now.

DS: Exactly. So you can live your life by yourself, Tami. I can live my life by my “self,” in quotes around the self. We would say, oh, we’re just independent beings. You’re there, I’m here and that’s fine. Then, when we start communicating with each other, we say, Tami’s there, Dan is here, and there’s a between-ness in our communication, in our respect, in our care for each other. It would be so beautiful to then say, let’s develop our relational connections. Let’s develop our interconnection. And even in different nonprofit organizations I work with, sometimes our mission statement says, “We want to have people realize the interconnected reality of life on Earth.” For years, working with those organizations, I’ve just felt fine with that, but then when I was in the forest and I realized that even the word interconnected falls short. I think what people really mean is that there is a wholeness to life on Earth.

So right now, in terms of the word intraconnected, I would say that there’s a kind of field that connects us—us meaning the body called Tami, the body called Dan, and the body of every human being that’s listening. And within that wholeness then, right in this moment, when I even start to use the word intraconnected, and this may sound maybe too much, but when you feel it, it’s just a feeling of the reality of it, the body called Tami is me. The space between us is me. It doesn’t feel, when you drop the separateness that’s connected—which is what the interconnected word means, two things are connected to each other—when you let go of the entity experience where the entity has a separate quality, that there’s the body, Tami, the body, Dan, this feeling of an identity that’s bigger than the body allows us to feel that the Tami, Dan, and everyone listening experience is a kind of—I mean, we use the term relational field, which sounds kind of maybe too not specific.

There’s a wholeness within the relationality where you no longer speak from the individual parts, but you’re speaking from the wholeness of it all. So the journey you’ve been on to make Sounds True, the journey this body of Dan has been on, about interpersonal neurobiology, in many ways, they’re the same journey. So when you reached out and said, “Would you like to do this experience of a conversation?” The feeling was, humans need this conversation. It isn’t even a conversation between me and you, this is a conversation for our whole human family. So that’s the intraconnected nature when you just look at the system of humanity. Then, when I think about what those trees literally said to me when I was in that forest, those three days, and this is going to sound odd, and I’ve never actually said this so publicly, I don’t think I’ve ever said it, said in that small group, the trees spoke to me and said, “Protect us. You’re in a human body and humans are destroying us.”

These are the aspen trees in Colorado way up there. They said, “Protect us.” I was like, whoa. Now, you could say, oh, Dan is just hallucinating. But whatever it is, the feeling was I got a message. It was in English, “Protect us.” Those words and the message in this body was then carried out through the word intraconnected that, yes, I have to act on behalf of. And part of the book, IntraConnected, is saying we need to act on behalf of those trees, of the whole system, because we’re too separated. Even with the word interconnected, we’re still here and I’m there and we’re separate. So how do you actually start feeling into the reality of the intraconnected whole? So I don’t know, how does that feel for you?

TS: Well, so the part about the trees talking to you doesn’t sound that weird to me and saying, “Protect us.”

DS: Okay.

TS: That part made perfect sense.

DS: All right.

TS: I think the place where I had a moment was when you said that body over there—I can’t remember exactly what you said— it’s my body too. It’s our share, and that’s where I think, well really. When you start talking about the body, especially where people say, “Hold on a second. I woke up, I went to the bathroom this morning, Dan wasn’t there with me. This was a private moment that I had.” I’m just using a gross example to be funny. I’m just trying to say, or especially if our body is suffering in some way and your body isn’t, there’s clearly some real distinctions going on between our bodies right now. I have a disease, you don’t, for example, someone might be thinking. So help me understand the intraconnected perspective when it comes to the sense of having a separate body.

DS: Yes, absolutely. So one way to think about it is, and this is where the subtitle MWe comes in, where the intraconnected wholeness is not about giving up the differentiated inner experience that as Tami, you have in that body going to the bathroom or that Dan, this body going to the bathroom, having a disease.

TS: I’m so glad we brought it to this level, Dan.

DS: Yes.

TS: Yes.

DS: It was body talk. So we have the reality that you have an inner experience of self and yes, your inner experience is differentiated; it’s distinct, as you’re pointing out, from that of this body. Then, there’s an inter-experience, which is the communication we’re having with each other now and when you put the me of the inner and the we of the inter together as MWe, then you realize, whoa, that’s like the wholeness of it all. So in the forest for example, yes, I had to do what this body needed to do to survive those three days, and the trees were doing what they did with their roots and their leaves. So we had the inner and we had a way of communicating with each other in an inter, and there was the intra, just to introduce that notion that was the wholeness of it all.

So that, it wasn’t as if, oh, I heard the trees speaking to me, let me protect them. It was more like their inner experience called out for protection, this body as a human body might be able to do something like continue working for ecological protection, maybe write a book on IntraConnection, maybe speak to people about all the things we can do to protect life on Earth, which is related to other things like social injustice that we can get into. So then it was this integration, I would use that word, of differentiating the inner and the inter and bringing them together as the intra. In some ways, it’s like an identity lens where yes, you have an identity lens of inner, that’s Tami and I have it as inner, as Dan. Then there’s the Dan-Tami relationship and then, there’s the Dan-Tami relationship with everyone listening to us right now.

Then, there’s the wholeness of it all, and I don’t know what words we have in English for that, but the notion of MWe tries to capture that, that we are both an inner and an inter and there’s a wholeness to being the whole system of life.

TS: I think it’s so important to honor all three, the inner, the inter, and the intra in the way that you’re describing Dan, because I think one of the things that happens is sometimes when there’s this focus on our—I’ll use a word that you don’t use, but people sometimes use—our oneness. There’s a sense of there being an erasure of our uniqueness, of our differences, of our distinctions. There’s something about that that feels offensive in a way, like don’t take away what has come through my biological lineage, that’s unique in my experience, whether that’s of ethnicity or my DNA strands or whatever it might be. So help me understand how we can—and you do this so beautifully in IntraConnected—have this deep honoring and respect for what makes us different while at the same time, we’re connecting to what is our intraconnected shared fabric.

DS: Yes. Well that’s so great, the way you’re articulating that Tami. In trying to go from that experience in the forest to seeing what might be done through action in the world, I started—because I have this addiction to writing books, I started pursuing how to get these ideas together. I actually assembled a group of about two dozen people from all walks of life to do a pre-book book club to offer insights into what they would like such a book to be, for it to be useful across all these different backgrounds that they had—racial backgrounds, gender identity, sexual orientation, education, culture, age. It was an incredibly diverse group. That input was very important to seeing how to put words to this and then, turning to Indigenous teachings, which in many ways, for thousands of years, have been teaching this, as have contemplative practices for thousands of years independently.

When you find a common ground across independent pursuits, E.O. Wilson, the sociobiologist, who passed recently, he names that “consilience.” So that’s a beautiful term from E.O. Wilson’s bringing back from the 1800s actually, that word, consilience. So the Indigenous teachings from millennia, from thousands of years ago, contemplative teachings, have taught about the oneness of things. Now, in modern times, in science, for example, modern Western-based science, we have the field of anthropology, which might say there’s an individualism within, for example, the United States. Then, there’s collectivism where you lose the individual. And they talk about these two extremes that are studied, and I couldn’t find anything named that was in-between, that said, can you have an honoring within this word “oneness” you’re bringing up?

Could you have something that was not going full-on collectivistic and getting rid of individualism, versus individualism that said do it on your own? That’s kind of where the MWe word came from. I had been giving talks saying, me to we, which rhymes, so I kind of thought that was fun. One of my students who is from the Lakota tribe, she said, “That’s offensive. Me to we, even though you’re telling us we should know our history, our lineage, our personal history and attachment, we should be in our bodies aware of our bodies. That’s all me.” I said, “Yes.” She goes, “But your title is me to we, and that phrase implies get rid of the me.” I said, “You are absolutely right.” She said, “Well come up with something else.”

So I said, “OK, not only me, but in addition the collective we.” She goes, “That’s too clunky.” So I said, “OK, well if you integrate something, you honor differences and you promote linkages, yet in the linking you don’t lose the differentiation. So I guess you would say me is real and we is real, so something like, I don’t know, MWe.” She goes, “That’s it.” So that’s when I started using the word MWe and it’s been—and I don’t know if this is what you were feeling, Tami, but it’s been a kind of liberating linguistic term, MWe and intraconnected, that say something—we don’t have to choose between oneness and individuality. You actually can have both. In some ways, it connects to what in contemplative teachings, especially in Buddhism, people talk about relativistic versus universal. And there’s some interesting science, consilience, that might help us understand that in other ways too, so that you don’t have to have either one.

Intraconnected, in a way, tells you you’re inner, you’re inner and there’s a wholeness to it all. So you don’t have to choose. You can integrate, meaning you differentiate the inner and the inter and even the wholeness of it all, and it’s all important, but they’re distinct and you can bring them together.

TS: Tell me more about linkage. In the book, you talk about linkage as an expression, we could say, or a form of love. So how does linkage integrate all of these distinctions and act as an activity of love?

DS: Yes, exactly. I mean the parenthetic, brief story about linkage being love, and this won’t sound maybe weird to you, but when it happened to me, it was unusual and I was kind of surprised. But I have this clinical practice, I have a practice as a therapist and two consilient ideas had come up. One was that integration, the honoring of differences, the promoting of linkages might be the basis of well-being. The second consilient idea was that for intentional change, we needed consciousness. So then I said, well, what if you actually brought those two together, what if you integrated consciousness? So then I had people differentiate the different elements of consciousness, like the knowns of your senses that bring in the outside world or your bodily sense that brings in the inside world or your thoughts and emotions and memories, things like that, and even your sense of relationality. What if you differentiate those from each other?

Then, you link them by moving this spoke of attention in this wheel metaphor, you move it around the rim and even ultimately bend it into the hub, which represents the knowing of awareness. So my patients in therapy started getting better. They started getting less anxiety. If they were mildly to moderately depressed, they started getting better. They started really feeling a kind of empowerment in their lives. If they were facing terminal illness, unfortunately, and having a panic about that, it could help them come to peace about dying, and it was really freaky for me. Like, whoa, I don’t know what’s exactly happening. So I thought maybe it’s just some quirky thing of my belief in it, or I don’t know. So I started teaching it to my students who were therapists. They started finding positive effects for themselves and their personal lives and for their clients.

So then I started doing it in workshops and before the COVID-19 pandemic, I did it with 50,000 people in person. And because I’m a scientist, I would pass the microphone around in workshops and say, “What was that like for you?” Here’s the linking and love connection, when people would bend that spoke around, this part of the practice, into the hub, all around the world, whether they had never meditated before in their lives or were teachers of meditation, when they would bend the spoke into the hub, a very common statement was, “I’m connected, I’m linked to everything and everyone here and I’m filled with love.” They would also say a phrase, “It’s empty but full.” And if I get the chance to ask them, “Well, what does that mean, empty but full?” They go, “I have no idea what it means. It’s just what it feels like.” Love, this open awareness, and this connection. Then, I started wondering if this universal experience—that is, I did this on every continent on Earth except Antarctica, where people would say in the hub of that wheel was love and connection.

Connection being a synonym for linking. Then, I started wondering, wow, maybe there’s something about the way—and this can get kind of abstract so I don’t want to get abstract, but the way energy flow can be understood from a scientific point of view, can give us some insights, which I’m happy to go into. But the bottom line is when you study the science of energy, energy can be seen in large accumulations we call matter. Then, there’s a lot of separation, both in time and space, but when you come to small elements, units of energy like electrons or photons, there are no longer these noun-like entities of separation, but there’s massive linkage and things are more like verbs. They’re unfolding processes with tremendous amount of connection, of linkage. I think the hub of that wheel, as a metaphor, is actually tapping into this microstate of science.

Physicists would call it a quantum realm. There’s two realms we live in. This microstate quantum realm is where this massive linkage and that in the workshops, these 50,000 people, those who spoke up, would talk about that linkage of love in the hub. So just as a scientist, what was shocking and kind of freaked me out was going, if I’m going to be true to being a scientist, where you doubt everything, you question everything, but you look at what the data is, it looks like pure awareness, linkage, and love are all part of the same fabric of reality. To be a scientist is to doubt everything and be super careful about ever saying you think something is true. So what I’m saying is just a lot of questions and a lot of question marks like linkage—

TS: Dan, let me make sure that people who are hearing about this Wheel of Awareness practice that you did all over the world with so many different people actually understand the practice. So is there a way you could just briefly, you mentioned it, but help us enter right now that sense of being in the hub?

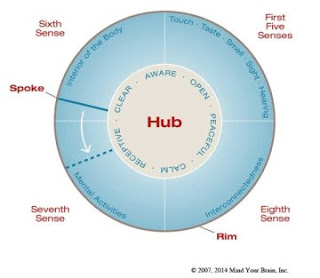

DS: Yes, well, I mean the best way to be in the hub is to do what I do every morning, is to do the wheels of practice. That would take half of our time, but I’ll just say that—let me describe what it is and maybe you could get a feeling for it just in the description. Imagine a wheel where there’s an outer rim and there’s a center hub. It’s actually a table in our office, and imagine a singular spoke, and this is a metaphor. So there is an actual table, but we’re just going to use the image of a wheel as a metaphor for what consciousness is about. The simplest way of looking at consciousness is that you have two things at a minimum in consciousness, you have the experience of the knowns of consciousness, the things you’re aware of, and then the knowing which is awareness. So when we talk about the word consciousness, it involves both the knowing and the knowns. The knowing, being awareness. The knowns being the thing you’re aware of.

Then, if you start with the thing you’re aware of, we’re going to put them spatially, in our metaphor, on the rim. And we’ll divide the rim into four parts. I think they’re about energy flow patterns. So I’ll just phrase it that way. This is one hypothesis, but in the first segment of the rim are energy from outside of the body you’re in. So this would be what you see with your eyes, that’s photons. What you hear with your ears, that’s the movement of air molecules that are hitting your eardrum. There’s smell, that is, odors that you pick up, which is chemical energy. There’s taste, which is chemical energy on your tongue and also your nose. Then there’s touch, which is kinetic energy on your skin. So all of those are energy flow from outside the body and they’re the things that are the knowns.

So you move the spoke to each one of those, you differentiate them, take a deep breath. You move the spoke over to the second segment, and this is a segment where you explore energy from inside the body. So what does that mean? It’s the sensations of muscles and bones. It’s the sensations of genitals. It’s the sensations of organs, like your intestines or your lungs or your heart. One by one, we differentiate all of these elements on the second segment of the rim from each other. Then you take a deep breath after you’ve brought in all the signals from the body, whatever is coming and then, you go to the third segment, and this would be what we might call mental activities. Even though it’s all mental activities, this is probably the head brain because you have a brain around your heart and a brain around your intestine, which we just explored.

In this third segment, it’s probably mostly in the head, but it’s things like emotions, which come from body signals as they’re interpreted by the head brain—your thoughts, your memories, your hopes, your dreams, your longings, desires, beliefs, attitudes, all that stuff would call mental activities. In the first two segments, we did focus, attention.

Here, in the third segment, we shift to another pillar of mind training, if you will, where you’re opening awareness. You just say, bring it on. What’s in here? The fascinating finding is that when people say, bring it on, come on—even though when you do a breath awareness practice and a distraction like a memory comes up, you are intentionally letting the distraction go and return to the breath. Here you’re saying bring it on, and for many people who are bombarded by a monkey-mind chatter now, things get really quiet when they say bring it on. So it’s really fascinating, but there, what you’re asking people to do is just be aware of those mental activities. Then, to actually study them—how they first present to awareness, stay present, and leave awareness—and if they’re not just replaced by another mental activity, what does the gap feel like between two mental activities? We’ll talk about that gap in a moment.

Then, one of my clients said, “Can I bend the spoke?” I go, “What do you mean?” This is when I was first doing it back in the late 90s. She said, “Can I bend the spoke?” I said, “Why would you bend the spoke?” She goes, “I want to see what’s in the hub.” So I said, “Well, OK,” because we hadn’t done that initially when I was trying this out with my patients. So she bends the spoke around and that was the first time, and I wasn’t a meditator. I was just doing this like a reflective integration of consciousness practice. She said, “Whoa.” And she felt this incredible love. She was crying and it was just my patient, so I thought, OK, this is something unusual. She’s bending this spoke, what an interesting idea.

After doing it with thousands of people, and this is the common experience, and I certainly get it when I do it every morning, there’s a feeling like you’ve entered a different realm, almost like you can walk on the land and that’s one realm.

You jump into a lake and the properties of swimming in a lake are just different from the properties of walking on the land. No one freaks out that you have two realms of water and land. This is something that physicists are telling us. We have two realms in one reality. We have the macro state realm of the body, large things like molecules or an apple falling from the tree like Newton studied or planets, these large objects and they are now like entities, but then there’s this realm of small things. Anyway, so there was like, she had this experience and then people—I made that a part of the routine, to bend the spoke around into the hub or just let go of the spoke and just be in the hub. Then, when you straighten the spoke out and go to the fourth segment, that’s your relational connection.

So people you know, your spouse, your friends, your colleagues, your people who live in your community, people in your city, your state, your country, all of humanity, all living beings. Then, I presented this to Richie Davidson’s lab up in Wisconsin, they were so excited about this practice. And they said, “Well, why don’t you do lovingkindness statements?” I said, “This is just a science practice. There’s no evidence that shows that that helps.” They go, “We have the first study to show lovingkindness, metta, practices help, and it integrates the brain, and this was an integration practice.” So I said, “OK.” Then Barb Fredrickson, she found the same thing. So I put some lovingkindness statements inspired by Sharon Salzberg right in there, because they were science-based.

So then you end the whole thing with lovingkindness statements for all living beings to the inner me and then, I got in MWe. So you end the whole practice with MWe. And I was so happy because I couldn’t figure out how do I get MWe in here. But it ends with lovingkindness statements to MWus. And that’s the practice and it’s amazing, but it has the three pillars that research shows have all sorts of positive effects of improving immune system function, lowering stress, optimizing cardiovascular function, reducing inflammation by changing epigenetic controls, and even optimizing an enzyme, telomerase, that repairs and maintains ends of chromosomes. The bottom line of all that is it’s really healthy for your body to the three pillar practices: focused attention, opening awareness, and building kind intention.

So it turns out the wheel just has all three and you get this opportunity to explore things. In addition, you integrate your brain. You literally change the structure and function of the brain with three-pillar practice. So I do it every day, and when I sent the manuscript for the first book, Aware, about this, Elissa Epel had written the book with Elizabeth Blackburn, who got the Nobel Prize for discovering the telomeres and the telomerase that’s optimized. What they said to me when Elissa wrote to me in particular was, “You need to say in your book three-pillar practice, like the wheel slows the aging process.” I said, “That’s audacious.” She goes, “We’ve proven it. Elizabeth got the Nobel Prize for showing it. You’ve got to say it.”

So I had to add that audacious comment, that when you do this meditative practice, three-pillar practice, it actually slows the aging process.

TS: Now, in terms of connecting the practice, the Wheel of Awareness, with how we come to know who we are ourself, how we come to say “I am inner-, inter-, and intraconnected,” can you make that more explicit for me, how the practice maps onto that?

DS: Absolutely. Well, when people go through the IntraConnected book, which is both about conceptual knowing, called noesis, and also experiential knowing called gnosis, G-N-O-S-I-S, what I wanted to do was to have it be a journey. So I invite the reader to actually do the wheel practice. So I’m really glad you’re asking about this, as well as these nine domains of integration you explore. What people have shared with me, and I was hoping this might be the case, was that by combining conceptual knowing, these ideas we’re talking about, with the experience of—and I’ll say this in a way, you’re going to have to help me, Tami, because I can get kind of abstract. It’s just kind of how my mind works, but I think what happens is we’re born into a body for lots of reasons.

Life is hard and we really are driven for certainty because we have predictive brains. Basically, if we can be certain of what’s going to happen next, we’re more likely to survive. So because we live in a body, which is in this macro state realm of noun-like entities, of separation, we have an identity as an entity to give us certainty, but Rasheed, the artist whose quote is on the Brooklyn Public Library, it says, “Having discovered the flimsy fantasy of certainty, I decided to wander.” So a lot of us don’t wander. And in many ways, Sounds True, I think, is an incredible gift you’re giving to the world because you’re saying, look, there’s a journey of wandering past what modern culture tells us is what reality is. There’s something more, there’s different voices, but it’s one journey, as you beautifully say.

I think what Sounds True is really doing is—and this can be totally wrong—but I think it’s asking us to relax that flimsy fantasy of certainty that Rasheed talks about, to allow us to go from the certainty of the macro state realm of being in a body, of separation—there’s Tami there, there’s Dan here, there’s whatever your name is, in your body that’s listening—to then dip a toe perhaps into this other realm. Because what happens in that other realm is there are no nouns, there are only verbs. The Nobel Prize was given just recently for the establishment from physics, that what’s called non-locality is a real thing that is in the quantum realm, these microstates. So it doesn’t have to be something weird, but in the microstate realm, what in the Newtonian macrostate world we say are separation of noun-like entities, separating time, separating space.

In the quantum realm, that is not happening, and I could talk to you about the science, if you want to know about that. But when we dip our toe into that, even for a brief glimpse in the wheel practice, you can drop into that hub, which I think is the quantum realm, pure awareness. And I think there’s lots of meditative practices that offer it. The wheel just offers a really clear metaphor. Here’s the hub, here’s the rim. They’re distinct, which I think they are, and we have a macrostate realm on the rim where we think we’re all separated. So if you do the practice of the wheel, what it gives you experientially is a feeling of how deeply connected we are.

So we had a beautiful Congressman Elijah Cummings, who was an African American congressman from Baltimore. Elijah reached out to me and said, “We’re having a lot of murders in Baltimore. Can you come to Baltimore and do some work with people who are really not able to talk to each other?” So I said, “I’ll do it.” So I came and Elijah and I did a meeting of Black individuals and White individuals who had never sat in the room together before we got started. When people were just gathering, you could feel the tension. It was really painful. I do the Wheel of Awareness practice in the room with people who never meditated before in their lives, and I had done this in parliament, in Congress and all sorts of other places where I had similar effects, so I felt like this was a good thing to do in that setting, places of a lot of tension.

After people bent the spoke around into the hub and they came out of the practice, they started talking about how before they did the practice, they saw their separation and they didn’t feel like there was anything going to happen, but now, they could feel as they looked to the person of the other race that in fact, they were each other, they would use phrases like that, Tami. And Elijah was going, “What did you just do?” I said, “I didn’t do anything. I just gave them an opportunity to drop into the awareness that knows the truth of our connections.” I didn’t have the word intraconnected back then. So, the people in the room and Elijah Cummings was like going, “This is magic.” I said, “It’s not magic.” It’s a meditation practice that allows you to go on that journey and then, you quickly pop back out into your body, so they could leave and forget this.

Experientially, they know it’s true and in the IntraConnected book, the reason I invite the reader to do the wheel is because you can have any author, blah, blah, blah, tell you all sorts of things, and that’s the limitation of a book versus like—

TS: Sure, sure.

DS: So I wanted them to have the experience, so that’s the overlap. I think when you—even though I know people may find it abstract, I had to put it into the book because to really answer your question, which I try to do in the book, we need to understand why most human beings start with the experience of separation. I go through the developmental period from infancy on to adulthood and looking at these things in modern culture that reinforce separation, but then seeing those moments across the lifespan, infancy, toddlerhood, elementary school, primary school, adolescence, adulthood. I say, look, those are opportunities to make a difference in the world.

TS: Now Dan, I want to ask you about something you said. You mentioned that it’s our investment and certainty, in your view, that is one of the main factors that keeps us locked into this sense of identifying with separation, you call it in IntraConnected, the solo self. We want to feel certain. I’m curious what you think about this, because when I think of the investment in being separate, I think of something like a need to survive, like just the part of me that wants to make sure that I, the body, survive here. So that’s not really so much about certainty as it is like a survival drive. What do you think about that?

DS: Yes. First of all, I’ve just got to say this too, Tami, I love your mind. It’s so wonderful the way you think so deeply about things and see the clarity that is needed for us to go forward. So thank you, it’s such a joy to be with you. What I think about that is when you look—and I’m trying to parse through the different angles to approach this great question. When you look at, let’s say the cortex, the higher part of the human brain. People call that an anticipation machine, meaning it is always trying to anticipate what is happening next. And the way it does that is it seeks out patterns. The feeling of seeing a pattern is, I can know with some degree of certainty what is going to happen next. So in our cortex, in a way, we’re always living a step ahead of the present moment.

And it’s part of, I think the beauty of mindfulness is to try to get before that anticipatory brain. Now, the way the brain also works is it learns from experience, this cortex. So, the way it, number one, detects a pattern so it can know certainty, it then creates what are called top-down filters. So it says, “Okay, I know there’s a dog barking. I know it’s a dog. I know how a dog behaves. I know I could be careful, if it’s a wild dog, or not worry about it. So I’m going to put a filter on that bark so I don’t have to go, oh my God, amazing. It’s just a bark. No.” So through the top-down experience, I filter things through this lens of certainty so I can be certain, I know how a dog behaves, I’m going to survive. So certainty is the method of survival.

So you’re absolutely right. It’s about how do I, as a little baby, a toddler, a person at primary school, how am I going to survive? And I think part of why we need a journey towards, we could use the word spiritual for this larger sense of connection or personal transformation, whatever words we use for it, the reason we need it is that if, in modern culture, beginning with your parents and your teachers and your peers in school and then out in society, and the messages we get at work, and all of them are messages of the solo self that is about separation. The illusion of that is, oh yes, I’m entity. This entity is defining features that have certainty to it. So who I am in this identity, the features that define me is this body.

When I only put it in the body, and I use this acronym SPA, that the sensations, the S, the perspective, the P, and the agency of my selfhood is just about this body, it gives me some kind of certainty. When we expand that to realize, and my dear friend and colleague, Joanna Macy, Joanna beautifully talks about world is self and world is lover. In many ways, in writing this book and being close to Joanna, her inspiration for this body of Dan was, how do we actually allow people to relax that drive for certainty, which is a drive for survival? Because ironically—and this gets, I think, to the incredibly urgent importance of your question, Tami. The more—what people call them—the threats we have in the world of increasing social injustice and racism, of the polarization and misinformation, of the way people are addicted to screens, the loneliness people experience, and environmental destruction.

In many ways, you can call all those pandemics. They’re all around the world now. The viral pandemic, of course, another pandemic. All these things we could experience as threats. What the brain does with a threat is it closes down to try to achieve more certainty saying, who’s in the ingroup versus who’s in the outgroup? I want to keep the outgroup away from me, and if you’re in my ingroup, I’ll treat you with more kindness and care, but if you’re in the outgroup, I’m going to get rid of you in any way I need to. I think we’re seeing that on the planet now. So never before—well, I don’t want to say that. But now, we need in an intense way, maybe it’s happened before too. We need it in a very intense way to say, the natural reflex for certainty, for survival, is for separation.

We get this feeling of a lack of abundance, and then we constrict ourselves. Now we need, ironically, to actually even more go towards the deeply connected nature of our lives, because all of these pandemics, in some ways, you could say are either worsened by or even caused by the lie that our identity is only in the body, the solo self. So, writing this book, I knew it wasn’t going to be the popular book on the corner because it’s a hard request to say, even in the face of threat, let’s try to open up so that the quote “ingroup” becomes all of life, and maybe the outgroup becomes threats to well-being. So that when I said to Joanna, because she was saying a lot of the people she works with are burning out because they’re caring about the world and the world is in a tough place.

So I said to Joanna, because I have a dance background, I said, if the human brain is in a threat mindset, it’s going to burn out with fighting or fleeing or freezing or fainting, these four Fs of the threat state . And it’s OK for a few minutes or maybe a few hours, but you can’t sustain it for weeks and months and years. So what if we supported people, and this was the whole idea of the book in many ways, to go, OK, I can shift my mind to a challenge mindset. And instead of being driven for the certainty for survival, yeah, I can be about survival, but I see the bigger picture and I take on these issues of the world as challenges, not as threats, and then see them as dance partners. I wake up in the morning and I’ve been doing this myself, this phrase, what is the dance partner today? What’s the music of today?

Instead of seeing all these things that are happening that you say are horrible, and I’m helpless and “Oh my God, it’s terrible, terrible.” We can understand why people do that—because things are hard. But you can actually see them as challenges and see it as a dance that we take part in. Joanna was super excited about that, and that’s my hope of the gift of the book is to say, you know something, this is hard stuff. Here’s the abstract view of probably what it’s about, is we’re going Newtonian separation noun entities. So we want certainty for survival, but actually what we need to do to survive as life on Earth, is realize how deeply connected we all are.

TS: OK, let me ask you a practical question, which is the person who says, when I’m in a protected, peaceful place, maybe I’m taking a walk, I can feel the intraconnection, I can turn the spoke around. I can rest in the center of that empty hub, the empty wheel. I can rest there. Life is filled with potential. But when I feel scared, when I feel worried, when I feel the sense of threat, that’s not where I am. That’s not where I am. I actually experience myself contracting and I’m in a self-preservation mode. Come on, I bet Dan gets into self-preservation states too, and all of these great spiritual teachers, if you took a bunch of their money away, or if they had a bunch of people close to them who were ill, they might get contracted and feel the kind of threat that I feel, what do we do then?

DS: Yes, absolutely. Everyone is human and we can go on automatic pilot like that. There’s a story to address the question you’re raising, Tami, it’s a little painful, but I think it’s important if I can share it with you.

TS: Let’s do it. Yes.

DS: So if this starts to trigger something in you listening to Tami and me as I share this story, please take care of yourself. And because we’re facing so many difficult things, and Tami’s question, your question is so important, and it’s ultimate question because if we keep on going into survival restriction mode, we’re not going to make it. It’s going to be a serious, serious problem on Earth. So here’s the story. I was teaching at a workshop and we’re doing the Wheel of Awareness practice just as a sidelight. One of the researchers who was teaching with me, Dacher Keltner, gave the mystical experiences scale. When people came out of the wheel, when they got into the hub, and he got scores similar to as if people were on psilocybin, what people would do in research studies of psychedelics where they were feeling open and connecting and stuff like that.

So we were all kind of in that and then, one of the participants raised his hand and he goes, I have a story I want to share with you. And I’ll change a couple things for his own privacy, but he says, my two adolescent daughters, I had this terrible thing happen and people thought I had lost my mind. So, they said, dad—they read my book Brainstorm, for adolescence. And they said, you have to go to hear this guy Dan Siegel speak at this workshop. So he came to the whole workshop, he’s not like a workshop-goer. He shares the following story. He was in a certain setting with a friend and someone came up to them and in front of him, his friend was murdered with a knife and then, the murderer turned to him and was murdering him, stabbing him in his neck.

It was terrible, terrible, terrible. The next thing we know in the story as he’s telling it, is he’s waking up in the hospital and they’re doing surgery on him and he survives. He is in this kind of peaceful state and people think he’s lost his mind. Why would he be peaceful after he’s been attacked like this? So he’s at home and his daughters then say, “Hey dad …” something happened, which I’ll tell you in a moment, “You need to go to this workshop.” Right before he came to the workshop, he was asked by the person who was arrested and now was on death row—I guess he was getting ready for a trial, it’s a long story. Anyway, he’s in prison and he asked to see this person he had stabbed. So this guy agrees to go and he goes. He’s with his friend’s murderer and his attacker. The guy goes, “I just need to know what happened.”

So the workshop participant says to the attacker, “What do you mean?” The prisoner, he says, “I killed your friend right in front of you, and then, I was killing you and you looked at me with such beautiful, loving eyes. I felt so connected to you.” The prisoner says, “I felt so much love coming from you, I couldn’t kill you, so I didn’t. But I need to know what happened.” And the guy goes, “That’s just how I felt.” As he’s telling us this in the workshop, he then says, “Now I understand why my daughters sent me here to the workshop. That hub is where I went in this horrible experience.” That’s exactly when I bent the spoke around just a few minutes ago in the wheel practice. That’s exactly where I was full of love, full of connection, full of this open awareness.

He goes, now I know, I didn’t lose my mind, I found my mind. Well, everyone hearing this is going, oh my gosh. And we all went out, because it’s a retreat, we were living together, we all went for food together and talking about stuff. We’re just chatting about it, but the hub, which is a metaphor for I think what I call the plane of possibility, this generator of diversity, this quantum state—from the science point of view, that’s what it is. But from the experiential point of view, to address your question. Sure, we can all go into reactive mode, fight, flight, freeze, and faint for sure. Sometimes we need to do that to deal with whatever is going on. This story, this is a true story of this event that happened, is I think also a metaphor for as life is happening and things seem like they’re murdering us, we need to go to that place, that hub.

We need to find a way to come from this place of love, so that we dance with what’s going on. In many ways, you could say that’s how he danced. He saw his assailant as a dance partner in that moment and just looked at him with linkage and love and that transformed the whole outcome. I think it’s the same thing with what’s going on now with racism. It’s certainly what Elijah Cummings and I experienced in that room. When you look at environmental destruction, when we separate ourselves as a species out from living beings, we’re using Earth like a trash can. So in all these ways, while it is an understandable automatic way, so your hypothetical questioner said, “I’ll bet Dan does this too.” Of course I do, because I’m living in a human body that has the fight, flight, freeze, and faint reactions to threat.

So part of the challenge is, I know we can do it as a human species, the bigger question is, will we raise our consciousness enough? I think at Sounds True, you have all sorts of pathways to do this. Joanna Macy has for decades been saying, we need a quantum change in consciousness. So what she was so amused about, about reading IntraConnected, was literally, this is the quantum change. Not just using that quantum word like, oh, it’s a big change, but it’s saying, I dropped beneath the noun-like separation of the Newtonian macrostate world and in reflective practices, I access this space of love. It’s as if the tapestry of reality is of love and connection. So that’s where this guy who was attacked teaches us, that it’s possible if you’re being murdered and that’s where you go, and he wasn’t the meditator.

It’s literally—and I think you’ve said this so long, Tami, in such beautiful ways. This is literally in each of us. So there’s something you’d call pervasive leadership. Each of us has the capacity to tap into that hub, to go into that spaciousness, and what emerges is our deep intraconnected nature, and this is where—I know we don’t want to create new words unless we have to, but in this sense and at least in English—and I haven’t found in any other language by the way. I keep on asking when I go around in different countries. Talking about the connectivity within the whole, from the sensation, S, the perspective, the P, and agency of the whole, that’s I think where human cultural evolution needs to move. I really think we can do this. The question is will we, and I’m hopeful we will if we have the right tools that are tools of the mind, and I think that MWe can do this.

TS: Dan, sometimes when people interview me, when the tables are turned, they ask me this question that I never know how to answer, so I’m going to ask it to you. They say, “OK, who are you, Tami? Tell us who are you?” I’m like, oh God, really? I don’t know how to answer that. So many different layers or dimensions or ways to answer a question like that. How do you answer that question, if I say to you, who are you, Dan Siegel?

DS: If I wanted to be simple and direct, I would say I’m energy. This energy takes many forms. It’s taking place in that body called Tami. It’s taking place now in the space of this conversation and anyone listening, it’s taking place in this body called Dan and the eye of sensation, perspective and agency that’s saying, what’s our identity, it’s energy. It’s raining here. I can see the plants. I’ve got a dog here. I’m energy, and that’s actually how it feels. In that energy is the linkage that is love. So it would be equally simple and equally real to say that I am loved. I say that as a scientist, Tami, I’m saying it—and you know, I was close friends with John, John O’Donohue. We would teach together and even though his background was different as a philosopher and Catholic priest and poet and mystic, we would teach together.

Even this book we were writing together was really about love. It was about transforming our ways of being on Earth in this deeply linking way, and we did it from these different perspectives, but we could teach—you would bring up homes and bring up things from Irish mysticism. I would say to John, “Well, what does it mean to be a mystic?” He goes, it was someone who believes in the reality of the invisible. I said to John, I said, “Well, I’m trained as a scientist and if I’m going to be true to being a scientist, I do know that the invisible is a part of reality because the human eyes can only see so much.” So part of what we don’t see, and certainly Michael Faraday in the 1800s saw it as electromagnetic fields, just to stay with energy.

By feeling this identity as energy, we can see it takes different manifestations. It condenses into matter, it manifests as love. It is the linkage among us. Even when my father was dying, Tami—and he was a mechanical engineer, steeped in Newtonian views of reality—and believe me, he didn’t show mindsight or anything like that, my whole life. When he was dying, he said—it’s unusual for him to ask me a question. Actually he said, “Where am I going when I die?” And I said, “I don’t know, Dad. I don’t know where you’re going.” He goes, “No, no, no. You probably have an idea about it,” and I thought—because he was a big yeller, he was going to yell at me right before he died, so I thought, I don’t want to get into this. So I said, “I really don’t know.”

He goes, “Well, just give me your view.” I said, “Okay, well, before you were conceived, all there was, was potentiality.” Of all the eggs in the world and all the sperm in the world, there were just huge potentiality, massive uncertainty in this open space, this place and then, one sperm and one egg got together and they formed the unique individual that you are, which given his personality like that phrase, you’re unique. And I said, “So then you get in this manifestation from possibility to actuality about a century to live in this actuality of this body.” I said, so my sense, I don’t know if it’s right or wrong, but my sense of what happens when the body is done with its century of being in its actualization as a manifestation of energy, it’s going to dissolve back into this sea of potentials, this plane of possibility.”

He didn’t know my work at all, but that’s what I was thinking about, this space. So I said, “That’s where you’re going. You’re going possibly to exactly where you were before you were conceived.” Well before I was speaking, his face was very caught and he was very nervous and terrified of dying. He was very close to the end and his face completely relaxed. He said, “That makes me feel so peaceful. Thank you.” I got to say this question you’re asking me of who are you, by going into this long journey, and IntraConnected is kind of the, I think, the word-based articulation in a book as best I can of this journey, of that identity, to say collectively, if we started feeling into that in the deep, rigorous way of using the word energy, then we can understand things even like death.

So I know for me, this body of Dan will only have so many years, like all of our bodies, and it’s changed my emotional experience and meaning of considering dying. Or my mom is 93 and getting near the end. That feeling in this body of Dan and the connection with her is just different with this intraconnected sensibility of things. So anyway, that’s what I would say. I am energy.

TS: And a few times, you’ve emphasized this notion of not experiencing ourselves as a noun, but instead in our verb-like nature. And it’s interesting, because energy of course is in motion. It’s izzying or something. What does that mean to you to be in the verb state?

DS: Yes, Yes. Exactly. Well, as Einstein said, “Energy equals mass time speed of light squared.” All that means really is that mass, like this cup or this body, your body, my body, they’re condensed energy. So energy is really what’s called a probability field, what that means is that when it’s condensed, it’s creating this experience, we would call with some degree of certainty. This cup is here, I pull it down, this cup is still here. Well, like that, but it’s a cup. In contrast, when energy has not condensed into matter, it is this moving dynamic thing. It’s still energy. What that means is that in a body, which is a noun-like entity, we can start having our minds, including our awareness, start to be tricked into thinking it has the certainty of matter.

That what matters in a sense, using that English mixed term, what matters is just certainty and stuff like that. When you drop into the verb-like unfolding and the massive connection of these verb-like events, then the question you asked earlier of, who are you? And now you’re asking for more specific refinement, that if you say your energy and it’s a verb-like—well, I think what does that feel like? What does that mean? In a way, what it’s doing is saying, wow, my awareness begins in this quantum state of massive connection. I’m aware that there’s a body called Dan that this awareness is in that has this certainty, momentarily anyway, in what in Newtonian terms we would call space and time. In the quantum realm, Tami, space and time as dimensions don’t exist, for all sorts of fascinating reasons. So it’s a totally different thing.

So in doing the Wheel of Awareness, for example, that’s the practice I do every morning. When I come out of it, there’s a feeling and I can only talk about the S, this subjective experience and maybe the P, the perspective, or maybe even the agency, the wholeness of it, of being a verb. It’s almost like life becomes more of a dance and issues that before this was kind of—a practice or a clarity might freak me out or get me really agitated or worried. It almost feels like there’s an opportunity to feel into the connection. So when you reached out, when you knew this book was out and I told you it was out and you reached out to me and said, will you be in this conversation? The feeling was this kind of, not just excitement that we’re going to be together and maybe people will hear about the book, which of course is exciting, but the feeling was like we as a humanity are—whether you call it relational field or culture or connection—we’re on this journey through time and space in Newtonian terms. But in quantum terms, we’re really on this unfolding of massively connected events, and when we bring to that, that love and connection and that open awareness, it’s like a portal through which this process of—it’s called optimal self-organization—but it’s integration where we’re allowing differentiation to be fully present, allowing linkage to be fully present. So in a sense, we become like portals that integration can move through in the bodies we’re in or the events we participate in. So if someone calls me and says, will you do this or that? I check in with my body and I feel, is this a portal through which more integration in the world will arise or is it going to decrease differentiation and decrease linkage, so it’s decreasing integration?

Then I’m not going to participate. If it feels like it’s an opportunity to let the portal release integration, then I participate, and that’s what I feel like this conversation is, is even if just one person can be inspired to say, wow, I can adjust this identity lens so that I can realize, yes, I am a noun as a me. Whoa, I’m also a verb as a we. And when I bring them together, I’m intraconnected in this integrated way. I don’t have to give up the me. I can also have the we taken together. That’s the intraconnection. Then, it’s a different way of us moving forward as a human family. It’s a different way to move forward as a human family that allows us to embrace this uncertainty that is, when you look at this graph, it’s maximal uncertainty.

This is why I think it’s so hard and why the journey of Sounds True that you have inspired ever-so-many people with and certainly interpersonal neurobiology, it feels like it’s coming to that place that when you open to uncertainty, you release the possibility of connection. And this is I think, this is this really incredible moment in our human family to do this. There’s a window to make a change in business as usual. Joanna Macy calls it “The Great Turning,” and anything that we can do to actually bring this Great Turning, which means instead of just the solo self of separation, we realize that we’re this MWe, this intraconnected wholeness. It is possible to do.

That’s what I hope this conversation can inspire people to participate in however it comes naturally for people to do, whatever their interests are, their talents, their situation in life. This is a pervasive leadership thing where everyone can be a leader in making this change happen.

TS: I’ve been speaking with Dan Siegel. He’s the author of the new book IntraConnected: MWe (Me + We) as the Integration of Self, Identity, and Belonging. The book is a deep contemplation into, who am I? What’s going on with me, we, and MWe and how do I open to greater potentiality moving through MWe right now? It’s a gorgeous book. I would go so far, Dan, as to say the book itself, page by page is a wake-up invitation to the people to MWe. So thank you so much. Thanks for all your good work and deep service.

DS: Thank you.