Growing Through the Cracks: A Conversation with Sachi Maniar

Over the past ten years, Sachi Maniar has nurtured breathing spaces for young people in the midst of profound intensity. When she first stumbled into the company of youth in conflict with the law, with runaway, orphaned and abandoned children, Sachi felt herself inexplicably at home. The work that blossomed from that feeling would eventually turn into a full-fledged organization that has now touched thousands of young lives, across three facilities in Mumbai as well as 18 other facilities in India.

At its core Sachi's work reminds us of each person's fundamental belonging, of the beauty inherent in wholeness, and the power and freedom that come from recognizing we are not the labels that others, or we ourselves place on our lives.

Learn more about her unique and heart-expanding journey through this in-depth interview.

Given the nature of the work being described, the following interview does contain some references to suicide and violent events. Reader discretion advised.

RICHARD WHITTAKER: Sachi, would you say a little bit in general about what you do?

SACHI MANIAR: With Ashiyana we create safe, positive spaces. In Urdu and Hindi, “Ashiyana” means home. We work in three facilities in Mumbai which are run by the government. One facility is for children in conflict with the law, children who are alleged of committing a crime. The other facilities are for vulnerable children who need care and protection, one is for girls and the other for boys. When we started we were a bunch of 20 volunteers who would go every Sunday to this facility for orphaned, abandoned, runaway children. We wanted to create a space where there was no fear and where children could be themselves. Children in institutions don’t feel a sense of agency. They’re ruled by the guards or older kids. Where there’s fear, there’s hierarchy, and there is no sense of power or choice. Through our work we create spaces where children can experience beauty, love, warmth, belonging. The organization we created through this work is called Ashiyana Foundation.

RICHARD: What’s the population of these places, roughly speaking?

SACHI: In Mumbai, each facility has anywhere between 50 to 100 children. But altogether, it’s around 3,000 in a year, because it’s a moving population.

PAVI: You’ve been working for ten years in Mumbai, where else are you working?

SACHI: We continue to work in Mumbai but during COVID, we got a project from UNICEF to work in five districts in the state of Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand. The program we created focuses on creating safe regenerative spaces in institutions and making the institution itself, a place of transformation and healing.

These facilities operate like prisons in many ways. Right? Children are locked up. Nobody’s allowed to come out; there’s very little activity. The people working there are not really interested in the lives of the children or their transformation. And they’re paid so little. Most of these officers are paid lower than a daily wage, so there is no motivation to do this work, and some of these places are also dilapidated.

In one of the facilities we went to, the children took us around and I said, “What can we do for you?” One of the boys said, “You can’t do anything. A lot of people like you have come and they promised many things.” I was like, “Well, let’s begin with one thing you can think of.” And in anger, he lifts up his bed an inch and puts it down, and I see thousands of little insects coming out.

I was like, “Oh, my God! I don’t even know how you’re living here!” So then we just spent time cleaning up the space. And this is how we build trust. Right? He was sure nothing was going to happen, but we were there because we were committed.

RICHARD: That would make a huge difference. How many facilities total and how many are with you in this work?

SACHI: We are working with 18 other facilities, and we’re a team of twenty people.

RICHARD: Do you have a title?

SACHI: What’s my title? Director. I've been hesitating to say that. [laughs]

RICHARD: Now what was behind your beginning to volunteer there? Where did that come from? How old were you and what were you looking for?

SACHI: It was ten years ago, so 25. I always wanted to do something, but never thought of starting something on my own. I would volunteer at different places. At that time, I met another social activist, Sindhutai Sapkal from a rural village in Maharashtra. She started singing in the trains and begging because she was thrown out of her family home after having a girl child. Today, she has a Children’s Home that has given shelter to thousands of orphaned children. Her story is amazing and rich. I told her I wanted to do something but didn’t know what to do; at that time, I wanted to find an organization I could be a part of. She said, “Don’t wait for the right moment. The right moment is now. Do whatever you can.” There have been so many turning moments. This was one was one them. I thought “Okay, let me just do whatever I can.”

RICHARD: In your background what gave you the wish to do this helpful work in the world? Your family?

SACHI: Yeah. I think I get this from my mom and my dad. My mom is the kindest person I've ever seen, and my dad did a lot of things for the community in Mumbai. He used to have paan…a type of leaf that is chewed as a mouth freshener and is common in India. My dad would go to this roadside shop and get it every night. He would greet the man at the paan shop the same way that he would greet someone rich. My dad passed away in an accident when I was nine. But when he passed away, the hospital was full of people who had come to see my dad. And we didn’t know them! It was just amazing, and I saw all of that. I was only nine and I don’t know where the bug came from, but yes, I've always wanted to be doing projects that help others.

After my dad passed away, we had a lot of hardships. I knew I had to make money and I focused on that. When I started college, I started working in the event management industry and one thing led to another. Somehow I got into the advertising and film industry.

RICHARD: You took this on because your mother needed help.

SACHI: Yeah. Now it feels like everything is just woven together like a web. Even filmmaking was a chance encounter. I started as an intern and went on to be an assistant director. I directed a lot of other non-profit films as a lead director, and then something else called out to me --this work with children.

RICHARD: And this was with a volunteer group. Where did that idea come from?

SACHI: A friend of mine, Tejal had rescued a few kids from the street and sent them to this facility in Mumbai. She kept following-up on them, and started a project called “Sunday Fun Day.” At that time this facility had bare, white walls. It was actually the first prison of Mumbai and was built by the British to hold freedom fighters. Later it became a juvenile facility for children who have committed crimes.

We gathered a lot of volunteers and on Sundays, we would paint the walls with the kids. When there were no more walls left, we said, “Okay, let’s screen a film every Sunday. Then we’ll do art, drama, music, and games together. None of the regular staff entered the facility on that day. It was a two-hour session from 2:00 to 4:00. Our volunteers reported at 1:30 and we did an orientation. Then we had a circle of sharing at the end. That’s how it all began.

.jpg)

A lot of kids would write down their names and phone numbers. They’d say, “Please tell my parents that I'm here.” I would come home with a whole list of numbers. I’d call the families. “Your kid is here. Did you know?" A lot of times they didn’t know and had been searching for them. They’d come and pick up their kids, and we’d reunite the families.

Then there was an old man who was trying to retrieve his son, but the officer in charge was demanding a bribe. He called and said, “I don’t have anything, what should I do?” I said, “Wait. I'm coming.” I went to the facility, and I just stood next to the officer until the whole process was completed. With me there, he couldn’t ask for a bribe. There were things like that.

Since my background is in filmmaking, I thought we’d make a film, to help raise money to improve the living conditions. We got permission initially, and I started going into the facility and making connections with the children. Then after a few days they said “Sorry, we’re withdrawing your permission.” They were scared. But, overall, we had such good relationships with them. Our first year was about building relationships with the guards. The guards and caretakers would be so nervous that we were entering the facility on Sunday. They would yell and scream at us. Four o’clock was a time of stress, for us and the children. Because four o’clock is when the children are counted. They’re counted six times in a day. They would beat up the kids, and line them up.

RICHARD: Who is “they” - the guards?

SACHI: Sometimes the guards, sometimes older boys who are put in charge to maintain discipline in the facility. It’s impossible, right, Richard? These guards were managing like 400 kids. And the whole place stank of urine. It was really bad. It was like just herding animals in a room.

RICHARD: So the guards are stressed out. Everybody’s stressed out. But somehow you got permission. But then they don’t want to look bad either.

SACHI: We made them look good.

RICHARD: So you built relationships with the guards. And you could understand their difficulties.

SACHI: We knew their stories, their family, the challenges they were going through. So, as we started working with the children, we realized we had to build a relationship with the guards, too. Honestly, some of them were really nice.

RICHARD: What kinds of problems have you had to deal with in the population you work with? There must be a wide range of issues.

SACHI: Yeah. At present, we work with children from the ages of 12 to 24. And a lot needs to be addressed. Everything from the need to be reunited with family, the need for education, legal support, help with employment or vocational training -- all of that.

But whether a child has committed a crime, or been abandoned, or sexually abused-- the problems faced are the same: the lack of self-worth, lack of space for expression, feeling lost. And the needs are the same: love, attention, belonging and just a space to express courage, freedom.

RICHARD: That’s a beautiful way to frame this. It’s so important to hear this articulated so clearly - that it’s the same thing we need: love, attention and a feeling of belonging. Pavi, before we began recording, you mentioned the separation of Pakistan and India and what things people brought with them, what they left behind when fleeing their homeland and how that was very revealing. And Sachi, you were saying …

SACHI: Some [juvenile correctional] institutions allow everything. Right? They’ll allow the pendant, the thread, the metal bracelet. Others won’t allow anything. They’ll just strip kids completely of any objects or belongings. It’s a very interesting thing to see, that where they allow things to be kept, the sense of identity still exists.

We did a circle where the children had to make something, an object that reminds them of themselves and their true self. Then we did a circle of sharing around what that object meant to them. A lot of kids would say the object “reminds me of my mother.” The connection to their mother is so strong. This is an institution where children were not allowed to keep anything, so this object became something that they cherished.

In another facility for children (ages of 5-18 years), who are orphaned, abandoned, went missing or ran away from their families there was a lot of sexual abuse going on within the institution, where older boys were abusing younger ones, and the culture of the institution was entirely polluted. The children had no idea or understanding of healthy boundaries. And when we entered the facility, it felt dead.

We were called to do a healing process in the facility. We gave them ice cream sticks and asked them to draw themselves on the sticks. We had them place the sticks inside small round bottles. The bottles were filled with water, glitter and little stars. The glitter and stars symbolized all the goodness, all the love, all the warmth, and everything that they wanted and needed in the world. Then we sealed the bottles and they became like – what are they called?

RICHARD: Like snow-globes?

SACHI: Yeah. Then, we said, “Every time you feel lost, you can just shake this bottle and remember all the goodness and love that is there inside you.” We even got a smiley ball and a black cloth to demonstrate. We said “A lot of times our smile is covered by a black cloth, just like how the sun is sometimes covered by dark clouds. But when we remove the cloth, the smile is always there. Just like the sun is always there behind the clouds. We did all of it very metaphorically. To show this world is always inside us - all the goodness, all the love, all the beauty, all the strength, courage -- everything is inside us. So every time you feel something overwhelming you just shake the bottle, and you will see the beauty again.” This was with little kids. It went really well and a lot came out of that.

RICHARD: I bet. Did you follow-up there?

SACHI: We did. The following year we went back. Through a 9-month program the children rebuilt their emotional language, did gardening, and reflected on their lives. We created memories that helped them heal from their past. We built the program with children every day. After they planted their garden each day, there were daily rituals where the children had to go and water the plants, and then sit next to the plants and write or draw something or speak to the plant.

PAVI MEHTA: You’re seeing the deeper roots - the abandonment, the lack of self-worth, the need for expression, and addressing that. But in the system, there’s a typecasting that happens right? How does the system look at these kids with addiction problems, or those who have committed extreme crimes?

SACHI: Yeah. When we entered the facilities, they told us these are not regular school children, so don’t treat them like that. They kept saying, “No” for activities, “no” for this and that, and they keep resisting us and pushing us back. It took us ten years. And now, in the facility that we’ve been in for ten years, you see they treat children differently. It’s not necessarily our doing. There are a lot of different factors, but the narrative change was helpful. Now they’re seeing the potential in the children, and what they’re capable of.

So, to go back, my mentor [Sonali Ojha] had created this beautiful metaphor of “the diamond.” We all have “the diamond” inside us. The diamond-being is pure. It’s kind. It’s compassionate. It’s loving. All the other emotions, like fear and anger might surround the diamond-being, but the diamond-being itself is pure. So the idea of uncovering the diamond-being in each of these kids, each of the adults, is essentially the work.

PAVI: I think about how many of these kids have not had any trustworthy role models in their life. They have had a troubled relationship with authority of any kind. How do you go about building trust in such instances? Now it’s ten years in, so you have the relationships, but in the beginning?

SACHI: I mean, kids are so honest. Right? They will tell you to your face who you are, what you are, where you’re bluffing - all of that. So, it was very clear early on: no lies, no false promises. We needed to be honest with the kids because they’d been lied to, abandoned and told stories that landed them here. So they did not trust adults. We had to create spaces which they could trust - like, “I'm showing a film, do you want to see it?” or, “ Let’s do some gardening and create a new space.” And once they invest their energy, their thought, and create a space and make it beautiful, then they’re ready for the circles -- or other activities in that place. And once the children start coming into the space we’ve created, slowly they start trusting. It’s a slow process.

RICHARD: They have to have [trust worthiness] demonstrated. Right?

SACHI: You have to prove it. I had a kid who was shuffled from one institution to another for five years. When he finally came to this one he was 17 or 18, and he said, “I have to tell you, I don’t trust you guys from non-profits. Nobody’s done any good for me.” I told him, “It's okay. Don’t trust me, but come for the circle. If I am able to change your idea of us great, but if it doesn’t happen, it’s okay. Just come for the circle.”

PAVI: What’s the role of the circle? What is actually happening there?

SACHI: The circle is one of the tools we use because it’s such an equalizer. There’s no boss; no one person is leading. So it becomes this space for equal expression. And because we’re talking about life experiences, not about theory, or any intellectual stuff, there’s an invisible thread that connects all our stories. And that builds the bond; it creates belonging, a sense of self-worth.

The children can speak at their own time, you know? There are kids who will not speak in the circle for a month, two months, three months, and then slowly will start sharing. So we give children the space to speak at their own time when they are ready. If a flower is in the bud stage, you can’t keep poking at it, saying, “It’s time. Open up.” You just wait. And the circle provides that space.

.jpeg)

PAVI: When behaviors come up that threaten the safety of the space, how do you navigate that? What is the typical response of the institution to, say, violence or bullying? And what is a different approach?

SACHI: We’re still learning this. I think the institution’s approach is to shut things down. We want to look closer and see what is going on, so we can get to the root of it. Shutting down only builds more anger and more divides. So, usually, when children are bullying, we will have one-on-one conversations with them and ask them why they’re doing that. And often, they’ll say actually, “It is not this. It’s something else that happened.” Most of the time it is something else. But it gets portrayed as-- they are violent, or uncontrollable.

So, we ask them questions to help them reflect on their actions and reach that clarity of, “Who do you want to be? If you don’t start working on that from here, what’s the point of you being here? Like every day in your life can just go by, or you can make it meaningful. So what are you going to do to make this day count?”

PAVI: You’ve seen so many stunning examples of transformation and perseverance, determination and courage. Are there particular stories where your breath has just been taken away by how someone has shown up for themselves?

SACHI: There are so many! There was this one kid who was 16 years old when I entered the facility. He was charged with an attempt to murder. This was in our first year of working with children in conflict with the law. We started by just sitting in circles with them, exploring different topics like happiness, sadness, kindness -- all these different things. Then one time the children said we want to organize Teacher’s Day. So, this boy was put in charge as the dance leader. Then on the day of the event I arrived, and I was like, “Nobody is ready! What are you guys doing?” I yelled at him. He turns back and says, “Who told you we’re not ready? We’ve been practising since 5:30 in the morning. Why would you say we are not ready?” I was like, “I’m sorry. Somebody told me and I believed them. I should have checked for myself.”

Then he went to a different facility. Over there, one day he hit somebody on the head, a driver of one of the vans. I took him aside and said, “Can you tell me why you did it?” He said, “I'm frustrated.” He removes his T-shirt and shows me all these marks. People in the facility were beating him up. He was released after that but was later implicated twice on false charges. We continued to keep in touch and kept motivating him to complete his education and start working. Today, he’s running his own mobile phone repair store. He got married with his own savings. It’s just amazing where he’s reached through his own resilience.

But we don’t have deep relationships with everybody. Like, Thursday morning I got a message from a youth who had come to us when he had turned 18. Back in 2016, we had started a group home for children who did not have a place once they turned 18. He was one of the boys who was there but then he stole, he cheated, and he used to smoke weed. All of this stuff was happening in the group home, so we closed it down. We were there to support him but he just left us in anger.

Recently, he happened to visit one of the facilities we work in. He met one of our team members, and told them, “I look at Sachi’s picture on Facebook and I feel happy, but I don’t have the courage to go speak to her.” I mean, he’s like, “I messed up, but I really want to get back.” Sometimes even though we might feel that we just lost a kid, in reality, maybe they were meant to find a path on their own--- and maybe they will come back at some point.

PAVI: How do you navigate your own emotional life? Because it’s not just one or two children you’re caring for. There are so many, and the current they’re swimming against is so strong—the personal trauma, the way society looks at them… Getting a job is difficult. Keeping a job is difficult - all of those things. How do you hold all of that? And in your ten years, have you changed?

SACHI: I don’t know. I never thought about it. I think every kid prepares you for the next kid you’re going to witness. The first time a young person tried to take their own life, I was panicking. But now I’m in a better position to handle a situation like that. The first time somebody broke my trust, it was so much harder. But now I know it’s a part of their journey. I think the children teach us how to hold everything. I don’t know about my own capacity, but everything we experience prepares us for the next experience in life too.

But how do I hold the grief and the trauma and the sadness of it all? I think it balances out because there are enough moments of joy and transformation and beauty and resilience. And there’s so much more that’s possible, and that helps hold everything.

RICHARD: Listening to you, Sachi, I can feel you have a gift - a capacity for equanimity and tolerance, for difficulty - that’s very unusual. And you may not be able to say anything about that.

SACHI: Yeah.

PAVI: Well, maybe Sachi can answer that question in a different way. Just give us a sample set of the kinds of calls, requests, emergencies that you navigate in the course of a week or a month or a day.

SACHI: So two months ago, my team member called from another facility and said, “They’re beating up this kid and we’re not able to stop them. What do we do?” They were beating him up because he was mentally ill. This kid had killed his mother and father both. It was very clear that he was mentally ill. He was 16 or 17 years old. But when I went to meet him in the facility, he was like, “I'm so happy you’ve come.” We had a conversation about how he liked mathematics. Our team been spending all this one-on-one time with him. We saw his potential. But one day, the counselors of the facility started talking with him about how he killed his parents. He got triggered and started beating up others. Then they started beating him up. So how do you navigate that? I think that’s the most difficult part, seeing the injustice and not being able to oppose the system. Seeing the inhumanness and harshness and having to keep quiet so that we can continue working with the children is the most difficult thing.

RICHARD: That’s an incredibly difficult case you’ve described. And he’s still in the facility?

SACHI: No, he killed himself. The facility neglected to give him his psychiatric medicines for a week or two, and his health deteriorated. Then they would get the other kids to take care of him or rather control him. The kids would beat him up or tie him up. In his last days, they would just tie his hands and his mouth and keep him in one room. So his health deteriorated and he was sent to a psychiatric hospital, which does not have enough resources. There, he jumped from the window. Somehow they managed to save him. But then after two days, he hung himself.

I wasn’t directly working with him; but there were two other team members at that facility who were numb, and traumatized. The kids in the facility wanted to know what happened, but the superintendent and the others said no one should talk about this to the children.

We planted a seed in our conversation, saying “These kids want to know. There is all this grief. We need to do something. Let’s plant a tree for this teenager. Let’s do a prayer. Let’s all come together and share what we saw in this child.” And we proposed this idea. The head of the institution said, “You cannot do any of that.”

So all of these kids are sitting right now with all of that questioning, all that grief, and not trusting the system. They’re saying, “I never get to know anything that’s happened.” So then we did an underground project, just managing emotions, talking with the children, taking them towards more positive expression - through drawing, painting, all of this stuff.

RICHARD: This is your creative response to the restrictions. It must be incredibly difficult.

SACHI: Yeah. It’s so frustrating that the people in charge think that when we talk about things, more will come up, so they don’t want to deal with it. They don’t have the capacity to deal with it. But actually, if you dealt with it, then all the frustration, anger and other things will not come up.

RICHARD: This has to be an endemic problem in such institutions.

SACHI: Of course.

PAVI: What kind of things do you do for helping someone navigate internally?

SACHI: The idea is to keep it forward looking and not go back into the past and moan because then it’s very easy to be a victim. But it’s important to acknowledge the past, too. So for example, we do this Step In, Step Out game.There’s a study that says there are three categories in which we face adverse childhood experiences. So we created a game out of it. You read out a statement, and then the kids step in or step out. Right? For example, we say, “If you never felt loved by your family, then step in.” Or, “If anyone in your family is in prison or has been in prison, step in.”

“If you felt like your father abandoned you or you did not receive the love of your parents, then you step in.” Poverty is a big one. So, “If you had to struggle for your day-to-day daily bread, then step in.” Those kind of things.

Most kids don’t even know that they faced these childhood experiences because of which they made these choices. This is a way for them to make sense of that. The idea is not to just keep it in the head. So there’s movement; there’s art; there is the visual aspect, and there’s the feeling and the sensations piece. The idea is to tie all of these things together.

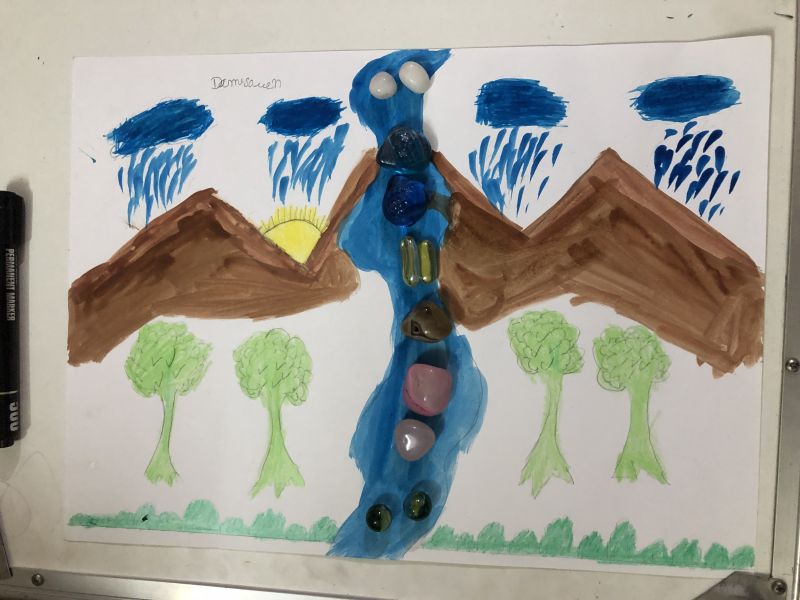

We also do a session called “River of Life” where the children have to draw their river-of-life. Then they have to write what were their experiences of people and places that shaped their life, or made their river turn a certain way, and eventually made them land up here today.

Then after that, the next thing is to say, "Okay. We’re here. This is an opportunity for us to change. You can make this an opportunity to change the course of your life, no matter whether you’ve committed a crime or not..” Like I draw this path and then I draw one line going up and one line going down. I say, “You are walking and you met with an accident, that’s why you’re in this facility. You have the option of going on the same path again, going downwards. Or you can go upwards, make this accident the best moment of your life, and use this time to make a change in yourself.” These are some of the conversations that we have with them.

RICHARD: It’s interesting the Step In, Step Out game. Whatever environment a child grows up in, they think it’s just how it is. So this gives them a new perspective. It seems like an amazing gift.

SACHI: Yeah. So that’s one part, and also, when we’re designing programs, the idea is to not do circles on sadness. We do circles on happiness. Sadness will show up as a part of that. And we keep focusing on what you have, rather than what you don’t have. Western psychology keeps labeling things. “Oh, you are ADD.” But there’s also something else, which is the gift of ADD. So how do you look at that?

RICHARD: And that’s a beautiful reframe. Do you have thoughts or examples of some of the gifts that can come from suffering, from deprivation. There’s a famous Leonard Cohen song:”Ring the bells that still can ring, There is a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in.”

SACHI: Wow. Yeah. Personally, I feel that suffering, like whatever bad happens in your life, can be a teaching moment. We see that in a lot of kids. Like we have some of the children who say, “I'm so grateful I was here.” We have one boy who is the first graduate in his family. He would have been a dropout, but the fact that he completed his education was because of the facility. We have a lot of kids saying they were glad they were here.

RICHARD: I understand that you have some relationship with John Malloy? Do you want to say something about that?

SACHI: Yeah, it’s a deep relationship. John is a mentor, a guide. He’s more of a guide for my own journey, so that’s been really amazing. Most of the time, we’re talking about the kids, or the team, or how to do something, but it’s actually not that. And of course, John’s way of doing things is so unique and beautiful. It helps me not get lost in a term I learned recently - “the non-profit industrial complex.” Or getting lost in how to grow the organization. His focus is always on, “How do I support children’s journeys? Who do I need to be?” He’s always reflecting that.

Pavi: You’re in India and he’s here in California, What’s your process of connecting with him?

SACHI: John and I have a monthly call. Usually, whenever I'm facing some issues, I write to him and share what’s going on. He’ll immediately respond or call back.

PAVI: Yeah. There’s one of the gifts of technology. And you know John, right? Each email he sends is like a little poem. And it’s often non-linear, too. Not like, “This is your problem. Here’s the solution.” I think when John looks at Sachi, he sees so much of the spirit of what he did at the Foundry, and what he continues to embody in the parent groups and grief circles that he runs. I think it’s more than a mentorship. It’s a very deep and unique exchange, a mirroring that enriches both, equally.

SACHI: Yeah.

RICHARD: If we could only have more Sachis and more Johns - what a huge gift that would be. I don’t know how we actually move in that direction, but sharing this helps.

PAVI: What I’ve felt, listening to the rawness of these stories, is that there’s no easy answer. A lot of it is sitting in the middle of the chaos and just kind of being present to it. Most of us in the outside world, we have so many pretenses in our social experience. So many ways of delivering false promises or being a little less than sincere. And there’s something in the stream of your work, Sachi ---there’s something very naked about it. You’re in this raw, very real place and you have to confront that in yourself, right? Like you said, the kids know when you’re bluffing. The way you bring forward the stories of these children, and the way you bring forward your own experience-- it gives us a glimpse of what sincere living can look like.

When you’re willing to sit with people in that way, it’s not pretty. But there is such a deep sacredness to that process. I don’t know if that makes sense or not, but I feel it very strongly.

SACHI: The way I define this work of entering institutions is easy, but the situation of the children in the institution is difficult. It’s difficult because any facility strips you away from being human. Right? That’s the problem.

So yes, I think the beauty is in the rawness of the lives of the children, and of everything. The beauty is in the paradox of how somebody can have nothing, and yet can be so kind and giving. How there can be so much anger, pain and evil, how can someone commit a murder or rape? There’s nothing good in those actions, but then in that same person, you see the light. You see the good things they’re capable of, and they you show that they’re capable of good. When you let everything come together then transformation and change happen.

So, I often think of what I see over there - those rocks and how the plants are growing in between the cracks. In India, you see this so much. You see a wall, and suddenly you’ll see a tree growing out of that, or little flowers. I feel like our work is that. The institution is this rock wall, the cement blocks, and if we can just grow through the cracks, that would be beautiful. This work is actually breathing life into these rocks.