Does Mindfulness Get in the Way of Making Amends?

According to a new study, one type of meditation promotes apologies—but

another one has the opposite effect.

Along its secularizing journey from Buddhist Sutras to scientific

laboratories to mobile apps, meditation has been adapted, dissected, and

distilled in many ways—in some ways for better (practices are

accessible to many, many more people) and in some ways for worse

(practices are conceptually diluted and commodified). Its first Western

incarnation, Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), focused squarely

on stress reduction and has been found to temper unpleasant emotions for pretty much anyone who puts the time and energy into doing it.

By Emiliana R. Simon-Thomas

But is dampening negative emotions always a good thing? A new study found that after we’ve done harm to others, a very popular mindfulness practice—focused-breathing meditation—may actually reduce our feelings of guilt and willingness to make amends.

The research team ran multiple experiments with online participants, as well as business school students in both Portugal and the U.S. First, participants reflected upon a past action that they felt guilty about or imagined committing a harmful offense, like engaging in questionable business practices, letting down their team, or accepting money they didn’t deserve. Then, some of them listened to an eight-minute or 15-minute focused-breathing meditation practice, while others were guided to let their minds wander or just browse the web. Finally, all of the participants were given an opportunity to do something reparative, like writing an apology letter or donating money to people who were harmed. Across the experiments, the researchers surveyed participants’ feelings of guilt, how much they were focusing on themselves vs. others, and their mindfulness.

The consistent finding was that compared to the mind-wandering and web-browsing groups, people who did the focused-breathing meditation felt more mindful and less guilty, and in turn showed less reparative behavior.

These findings contradict a similar recent study that found people were more willing to apologize after practicing mindfulness, but that study did not measure guilt. Rather, the focus was on self-defensive states like anger and righteousness, and how mindfulness can reduce these after a transgression to promote apologies.

These contrasting results highlight two important questions about how mindfulness can influence emotions and behavior: 1) Could mindfulness promote apologies in some ways and discourage them in others, by swaying emotions like guilt and righteousness?; and 2) Are there specific ways to practice mindfulness that uniquely privilege particular emotional experiences and behaviors, like guilt and apology?

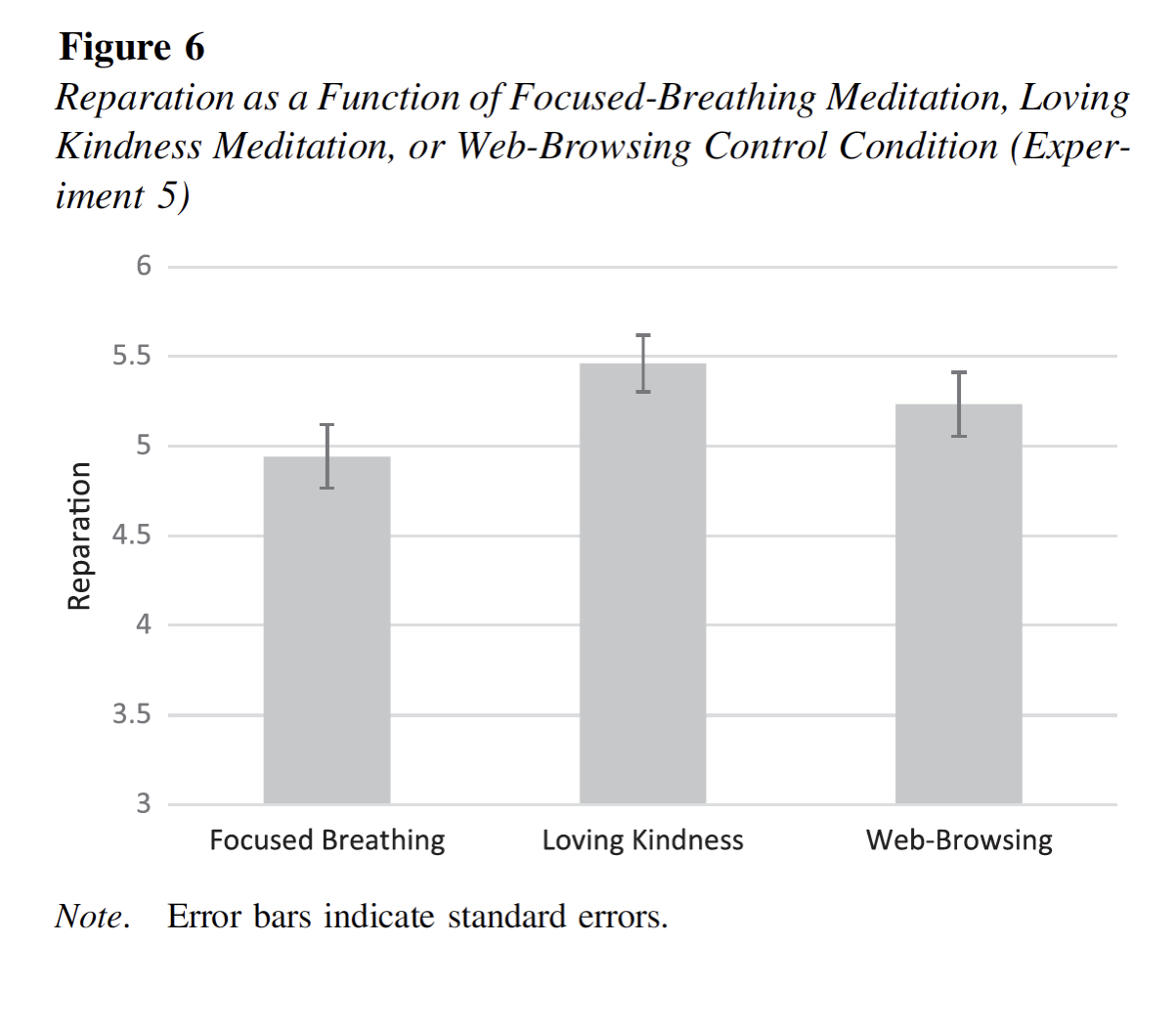

We need more research to shed light on these, but a final experiment in the current study touched on the second question. Here, participants reflected on a time they wronged someone they cared about, and then they either did a focused-breathing meditation, did a loving-kindness meditation, or spent the same amount of time browsing the web. Afterward, they indicated their willingness to call and apologize and engage in other reparative acts toward the person they wronged.

The result? While both meditations led to similar increases in mindfulness, only the loving-kindness meditation increased participants’ overall feelings of love, reduced their self-focus, and increased their willingness to make amends. Focused-breathing meditation led to the least feelings of love, focus on others, and reparation—even lower on average than web browsing.

Loving-kindness meditation appears to be a mindfulness practice that can help us welcome and leverage self-conscious negative emotions like guilt for interpersonal connection and growth, while still guarding against the tendency to ruminate until we feel anxious, depressed, or cynical.

These experiments point to the importance of honoring and embracing a diversity of emotional experiences, including the unpleasant ones. While feeling less negative in life is generally considered a good thing, and is even part of several leading definitions of what it means to be happy, there’s growing interest in the idea that each negative emotion matters in specific ways, and likely plays a formative role in happiness. Feelings like distress, sadness, or anger signal the importance of psychologically rich and meaningful, albeit challenging, experiences—and appropriately guide us through them. Negative emotions can motivate us to confront injustice, seek out support, or escape from harm. In this way, adverse experiences can be an important catalyst for learning, social connection, and purpose.

This study also points to the utility of varied approaches to mindfulness. An emerging theme in well-being science is precision, that is, understanding how specific individual characteristics, lived experiences, and contextual circumstances dynamically shape a person’s mental life and affect what kinds of practices are most beneficial to them. When we’re feeling guilty, we are better served by practicing loving-kindness meditation than focused-breathing in our effort to be more mindful, as it appears to preserve the reparative actions that guilt is meant to motivate.