How Well Do You Bridge Differences?

The results from our bridging differences quiz reveal how people of

different ages, races, and political orientations connect across

differences.

How good are you at connecting with people who are very different

from yourself?

By

Emiliana R. Simon-Thomas

The Greater Good Science Center created the bridging differences quiz to help people gauge their tendency to seek out, spend time with, and have meaningful interactions with other people whose backgrounds, beliefs, or positions in society differ from their own.

The 12-question quiz drew from several published tools for measuring factors that underlie bridging, like tolerance for disagreement, orientation to intergroup contact, and breadth of social capital. At the end, there are seven questions for quiz-takers about themselves: age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, neighborhood, income, and political orientation, which we analyzed to explore whether scores differ according to these demographic factors.

Almost 10,000 people completed the quiz. The average score across all quiz-takers was 3.79 out of 5, roughly 76%. Very pragmatically, this means that while a small proportion of people chose “strongly disagree” or “strongly agree,” most responses fell between “neither agree nor disagree” and “agree” for questions like “I am intrigued by cultural and ethnic differences” or “People who come from a different background are often more interesting to me.” The quiz also includes questions that indicate lower inclination to bridge differences, like “People who look different and act in ways I do not understand make me very uncomfortable.”

What did we learn? Read on.

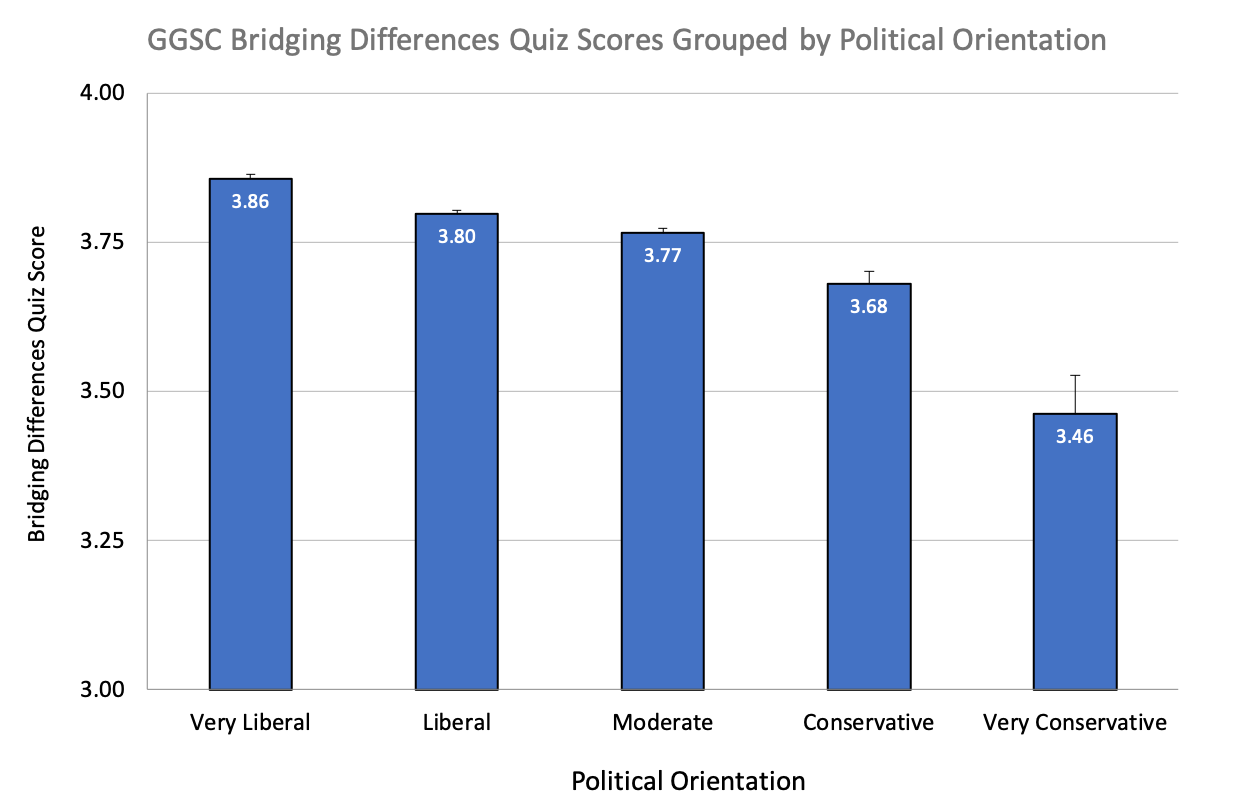

Do bridging-differences scores vary according to political orientation?

Yes. Here, we saw the most robust pattern of change in scores: People who rate themselves on the liberal end of the spectrum score higher than people who rate themselves on the conservative end of the spectrum.

This is consistent with other research. Generally, studies of liberals and conservatives report that liberals tend to think in less structured and more flexible ways, and to be inclined toward novelty-seeking and new experiences, while conservatives have a more structured and persistent cognitive style along with a preference for stability and order. Also, because difference-bridging is often called for in contexts of inequality, differences in how liberals vs. conservatives construe “fairness” might matter.

Specifically, liberals tend to define fairness as equal outcomes, while conservatives tend to define it as equal opportunity. While both political orientations value fairness, the liberal route is often progress and change, while conservative routes uphold precedent and tradition.

At its core, bridging differences is about embracing unfamiliar or unknown

experiences and the possibility of change, and this may run counter to

maintaining structure and conforming to the status quo, aspirations that are

linked to greater conservatism. These ideology-based factors may underlie the

inverse relationship between conservative political orientation and bridging

differences quiz score.

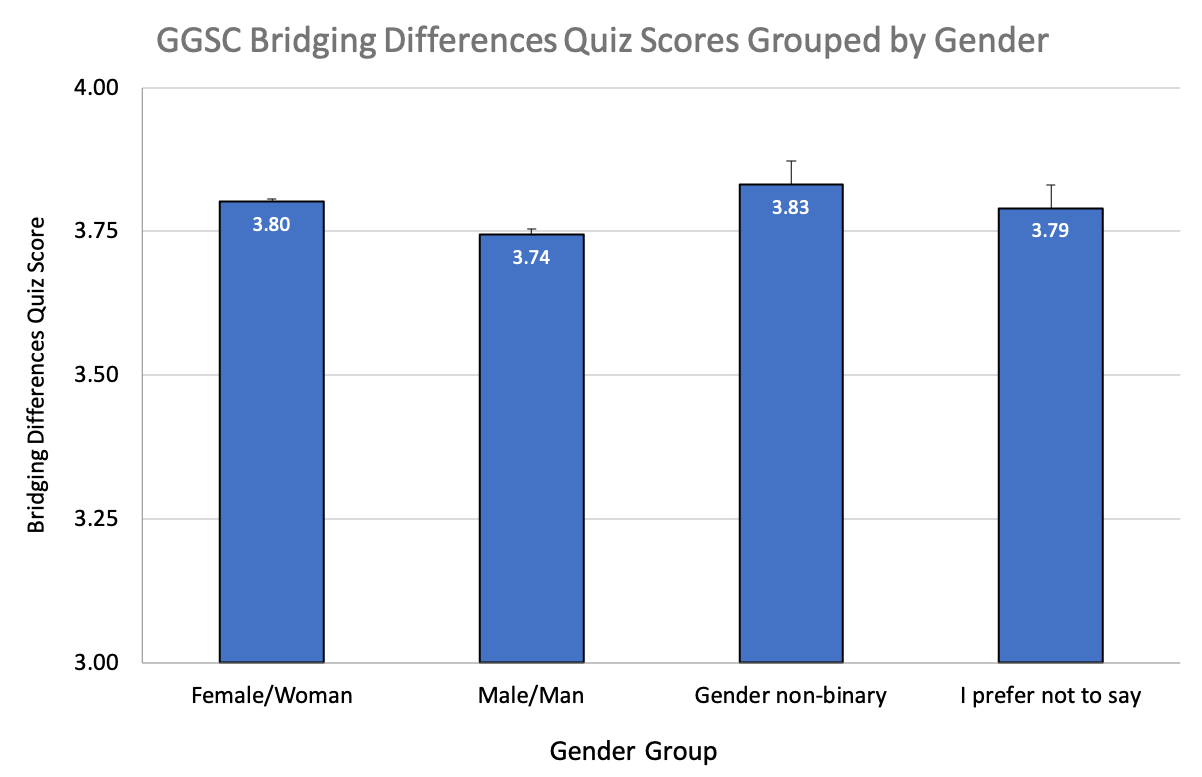

How did gender affect scores?

Women scored higher than men (3.80 vs. 3.74). It is common for women to score higher on surveys that are about friendliness, nurturance, or other prosocial characteristics.

While it can be tempting to seek a biological “men are from Mars” explanation for these differences, it’s likely that social norms are as responsible, if not more. In general, the scientific literature on sex differences in complex social behavioral tendencies (like bridging differences) lacks evidence to pinpoint where these kinds of differences come from. It’s also important to point out that average differences between groups don’t tell us much about individuals in those groups; we cannot assume that a particular woman will just be better at bridging differences than a man. And the data show that anyone, regardless of sex, can get better at bridging with practice.

While the average score from gender non-binary quiz-takers was numerically highest (3.83), and that from people who declined to state their gender was nearly equal to female quiz-takers (3.79), there were no statistically significant differences between the scores from these two groups and the male or female groups. Score differences may reflect disparity in sample size (there were many fewer people in the gender non-binary and “decline to state” gender groups), or variability (there were bigger differences among the scores within these groups than the male or female groups). With a greater number of gender non-binary and “decline to state” gender quiz-takers, we could gain a clearer picture of the ties between gender and bridging differences.

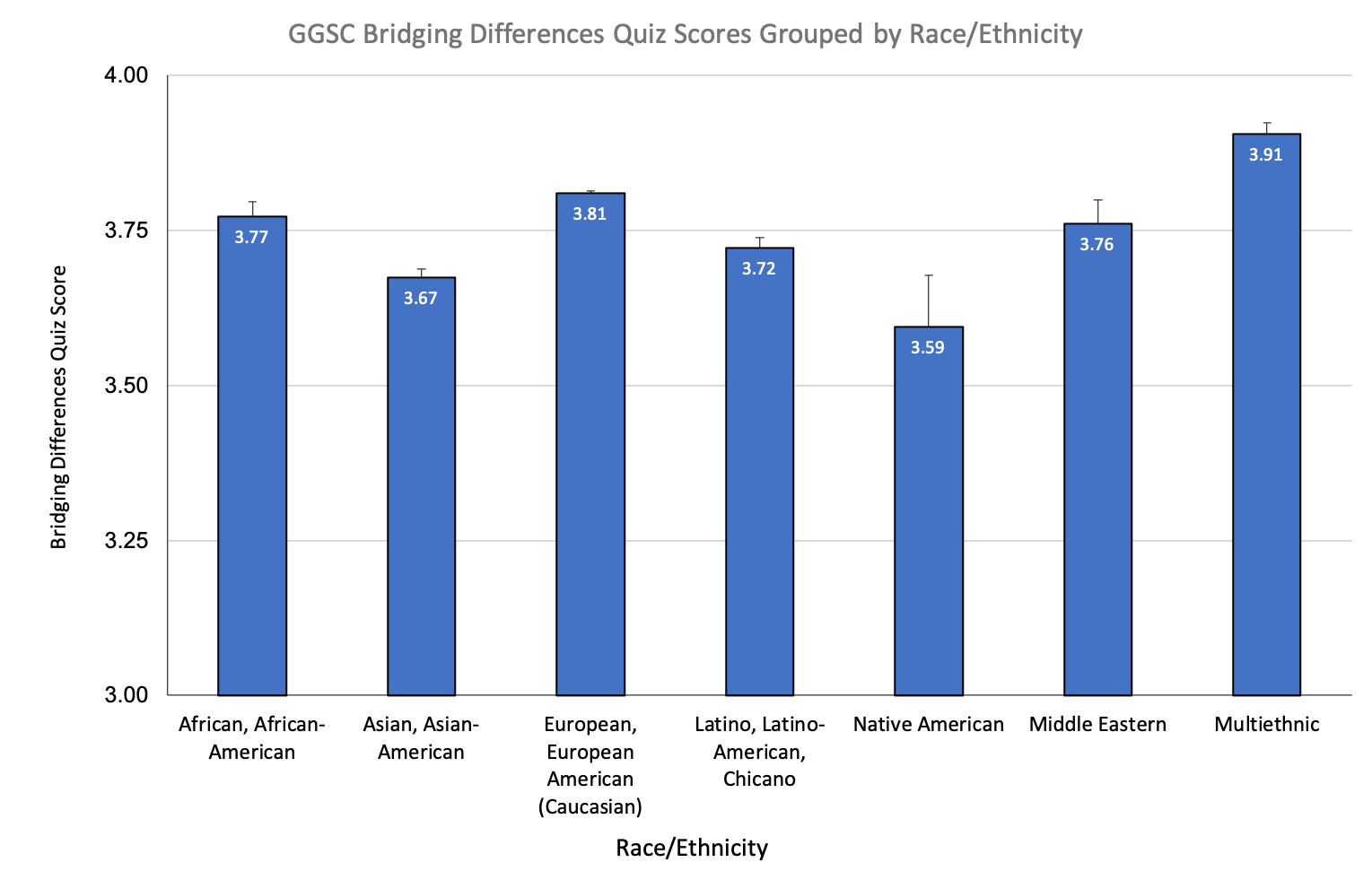

What about race and ethnicity?

The race/ethnicity question that accompanied the GGSC bridging differences quiz offered the following options: “African, African-American”; “Asian, Asian-American”; “European, European-American (Caucasian)”; “Latino, Latino-American, Chicano”; “Native American”; “Middle Eastern”; and “Multiethnic.” (Quiz-takers could also write in a response if none of the options provided were appropriate, though this free-response data is not included here.)

People who selected “Multiethnic” scored highest, followed by people who selected “African, African-American” and “European, European-American.” The next highest quiz scores were from people who selected “Middle Eastern,” followed by a cluster of very similar scores from people who put themselves in the rest of the categories. As with gender, these results reflect complex cultural norms, not inherent differences, as well as systemic and structural factors.

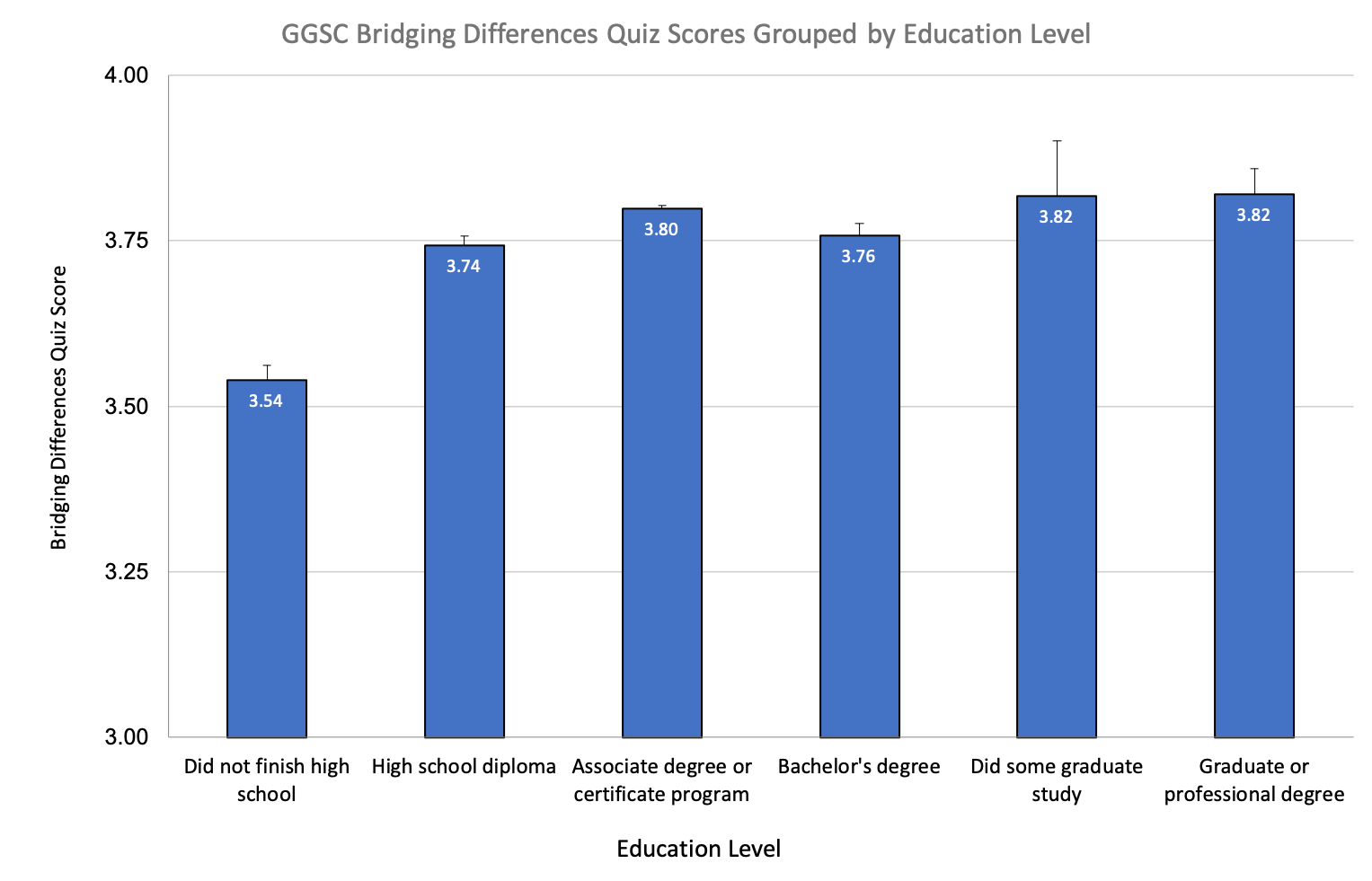

Were scores related to education?

People who hadn’t graduated from high school scored lowest on the bridging differences quiz. People who completed high school or earned an associate’s or bachelor’s degree scored higher, and similarly to each other. There was another slight bump in scores among people who reported having completed some graduate work or earned a graduate degree. The differences from group to group were not huge, but there did end up being a significant gap between the highest and lowest levels of education. So, more educational attainment does seem to contribute to people’s ability to bridge differences.

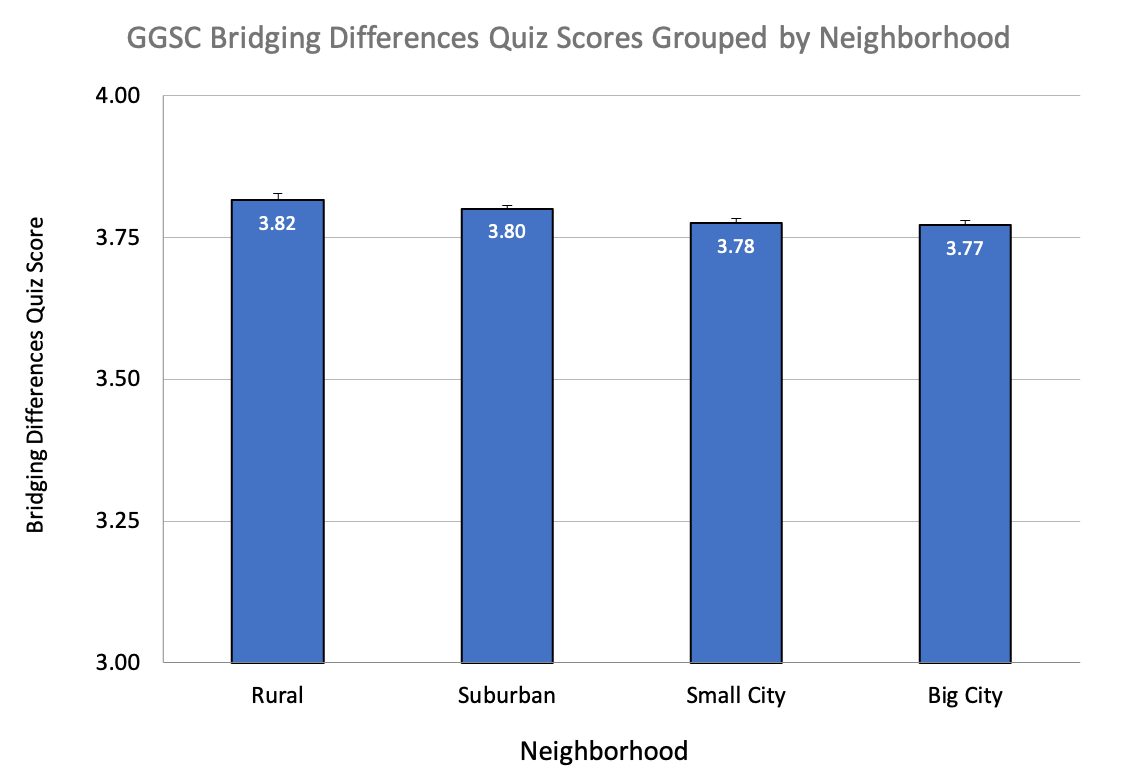

What about rural vs. urban neighborhoods?

People from rural and suburban neighborhoods score slightly higher than people in small or big cities. While this might sound counterintuitive, given that city-dwellers likely have more access to a greater number of diverse and multicultural fellow citizens, there are two plausible counterforces that might explain this pattern.

The first is that cities may be more ideologically homogenous to begin with. The second is that given the greater number of people living in cities to choose from, city-dwellers may gravitate toward those who they have more in common with, and who share their own ideals. Residents of rural and suburban communities, on the other hand, may find themselves having to embrace the people whom they live near, regardless of similarity.

In addition, our quiz probably wasn’t subtle enough to really get at how people in urban and rural areas perceive and negotiate different kinds of differences. For example, religion may loom larger to respondents in rural areas, whereas race or language may be something urbanites need to negotiate.

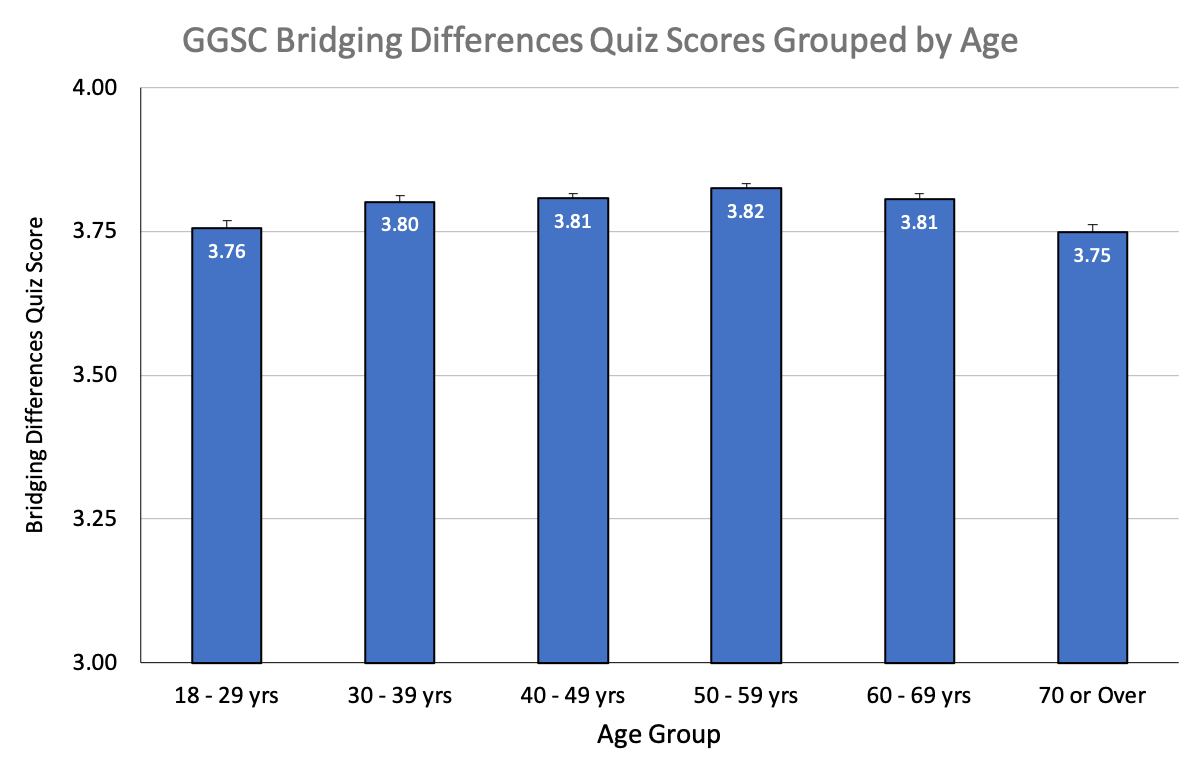

Does age shape bridge-building?

Organizing quiz scores by age groups spanning from 18 to over 70, responses show a very slight upside-down U pattern. Quiz-takers in their 20s scored lower than quiz-takers in their 30s, 40s, 50s, and 60s, and the same as quiz-takers in the 70s. In other words, it seems that we are most open to connecting with different kinds of people in the middle section of our lives.

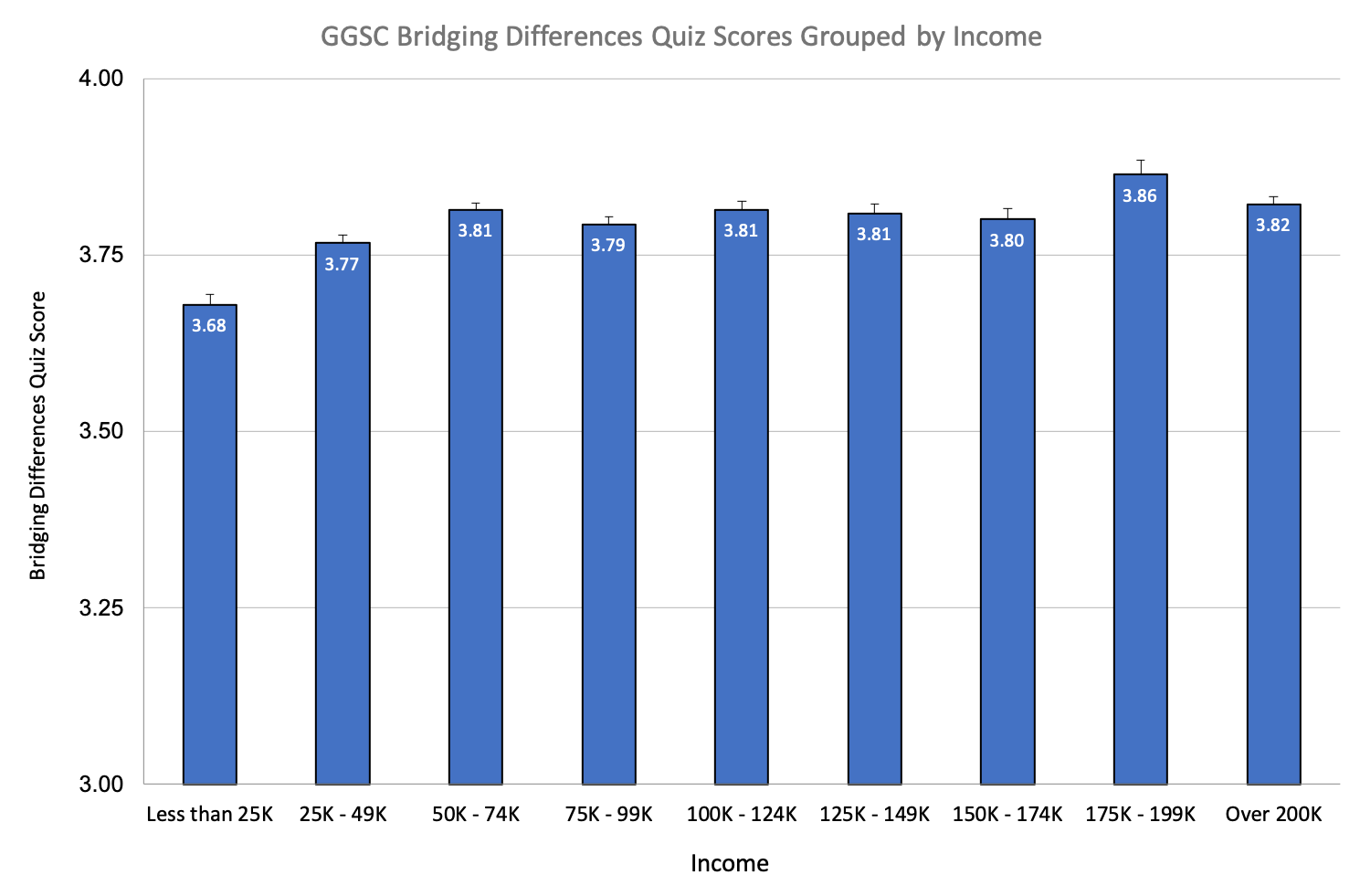

Does wealth influence bridging-differences scores?

People who earn the least (less than $50,000 per year) have lower bridging-differences scores. Between $50,000 and $200,000+ per year, bridging-differences scores pretty much plateau, showing no systematic pattern of increase or change related to income.

This quiz has a lot of limitations, and these results are not peer-reviewed or scientific. However, the GGSC bridging differences quiz does offer us a chance to reflect on our own tendency toward affiliating and connecting with people we feel dissimilar to. It can also give us some perspective on what kinds of factors might inform patterns of difference bridging.

Emerging evidence suggests that bridging differences affords many advantages and leads to greater progress and ease on every level, from the neighborhood to around the world. The good news is that building bridges is a skill that anyone can learn—and the Greater Good Science Center offers many resources to help you develop your own ability to connect across differences.

For a start, you can check out our Bridging Differences Playbook. For a more thorough and immersive learning experience, you can join the Bridging Differences course on edX. Or you can just follow our many articles on the topic.