How Socially Connected Are You?

The results from our social capital quiz reveal who feels the most socially connected, both in person and online.

Do you feel part of a larger community? Are there people you can reach out to for support?

If so, you might have plenty of social capital, which includes our social ties—family, friends, partners, coworkers, neighbors, even social media followers—and the benefits these ties afford us. We measured our readers’ social capital with a quiz we published last year. The responses from 36,000 people reveal a great deal about the nature of social connections in the twenty-first century.

Social capital refers to family and friends who support you through difficult times, as well as neighbors and coworkers who diversify your network and expose you to new ideas. While social capital originally referred to face-to-face interaction, it now also accounts for virtual interactions online such as email or on social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and LinkedIn.

Social capital refers to family and friends who support you through difficult times, as well as neighbors and coworkers who diversify your network and expose you to new ideas. While social capital originally referred to face-to-face interaction, it now also accounts for virtual interactions online such as email or on social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and LinkedIn.

Social capital also includes the rewards these social connections yield, such as the feelings of bonding and belonging felt in close friendship, and the expanded worldview you might get from looser, broader connections. And these benefits trickle down to many parts of life; social capital is associated with happiness, better job prospects, cardiovascular health, and positive health-seeking behavior. Among seniors, social capital has been linked to physical mobility and tends to reduce cognitive decline.

Recently, with the growing prevalence of smartphones and socializing via social media, people are looking at social capital differently. Some people wonder how technology and virtual connections are impacting our social capital in the “real world”—does technology cut us off from others? Or does it actually make us more connected? Recent research emphasized that social media is helpful in maintaining relationships, though harmful if it is used for superficial interaction or to replace face-to-face connection.

Last year’s social capital quiz focused on both the original, “in-person social capital,” as well as “online social capital.” (In the quiz, we referred to in-person social capital as “offline social capital,” which we have changed here for readability.) We asked our readers questions about how connected they feel to a larger community, whether they have someone to turn to in times of need, and how open and curious they are about new people, places, and things—both in-person and online. In reviewing the data, we calculated an overall social capital score, in-person social capital score, and online social capital score for each responder, and we looked at the trends among everyone who took the quiz.

About half of the quiz responders reported that they live outside the United States. To simplify the story, given that some of our questions are less relevant to people outside of the U.S. (e.g., education and income), the analysis here includes data from the participants within the U.S.

The average overall social capital score was 69 out of 100 (with a lowest possible score of 20), which suggests that folks have a fair number of contacts who may support them and expose them to diverse perspectives. When we looked into in-person and online social capital scores, people had much greater in-person social capital (80 out of 100) than online social capital (58 out of 100).

When we analyzed our U.S. readers’ social capital quiz responses, we found some interesting trends.

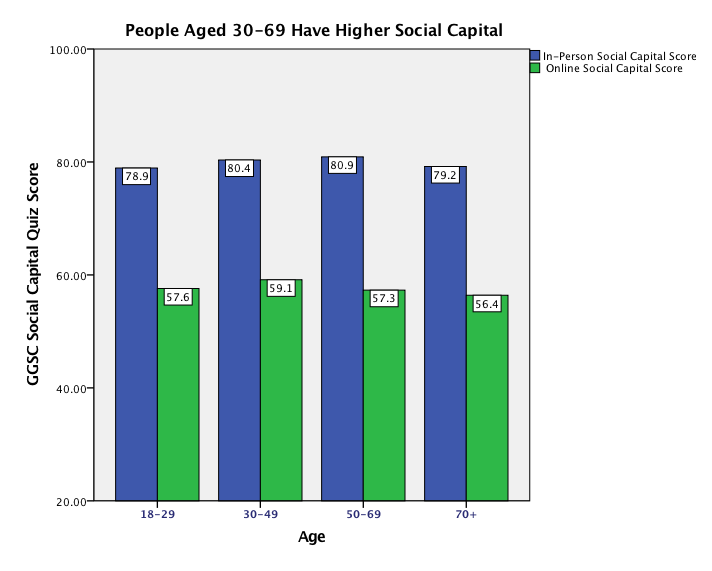

Young and old have less social capital than those in between. People under age 29 and over age 70 had significantly lower overall social capital scores than those aged 30-69. This pattern may be a function of 1) responders 30-49 having significantly higher online social capital than other groups (green bar, second from left), and 2) 18-29 and 70+ year olds having significantly lower in-person social capital.

The finding that people aged 30-49 had higher online social capital than the youngest group was surprising, given that millennials are suspected to be the highest users of social media. The Pew Research Center found that 88 percent of online 18-29 year olds use Facebook, a higher percentage than any other age group. People aged 30-49 had the second-highest social media usage across all platforms in the same study. Our data suggest that higher Facebook use does not necessarily correlate to building social capital. Younger people may not be using social media to build social capital, whereas 30-49 year olds seem to be engaging with social media in such a way as to increase connection.

That younger and older people had lower in-person social capital scores was less surprising, however. Perhaps these findings are accounted for by the fact that seniors tend to lose friends to old age or to fall out of touch with them over time. Similarly, in the U.S., many emerging adults move away from their family and friends for college, a job, or a fresh start in a new city, and therefore may have fewer in-person social connections during this decade of their lives.

Ethnicity did not affect social capital scores. Across eight ethnic groups, there was no significant difference in social capital scores, either in-person or online. Among our U.S. responders, at least, ethnic background had no effect on the social connections they had.

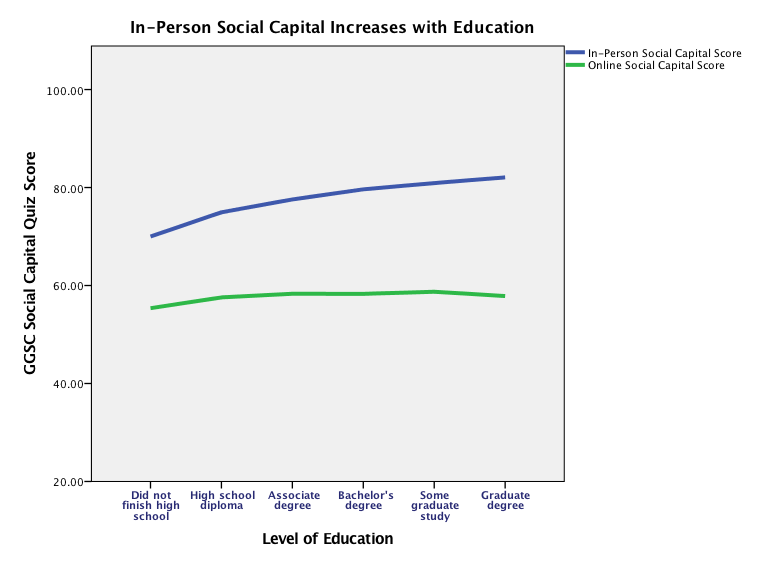

More education was linked to higher social capital. Among our readers, there was a small but significant positive correlation between education level and overall social capital. Those with a graduate or professional degree had significantly higher scores than other groups, and our readers whose final degrees were high school diplomas had lower scores on average. These differences seemed to be caused by in-person social capital; in-person scores tended to increase with level of education, while online social capital remained about the same regardless of education.

Our data cannot reveal the reasons behind these trends, but we have some guesses. Perhaps having many people to turn to may lead a person to more educational opportunities. It could also be that a high educational level opens doors to more social connections—maybe those with a graduate degree meet more people through school and work. Or, highly educated people are simply more sociable. Robert Putnam of Harvard purports that high educational level is a predictor of social connectedness, and that “highly educated people are much more likely to be joiners and trusters” due to their safe economic position and what they have learned at home and at school.

People in big cities had higher social capital. When we compared overall social capital scores across the types of neighborhoods our readers lived in, we found that readers who live in big cities had significantly higher scores than readers who live in small cities, suburban neighborhoods, and rural areas. This difference was accounted for by in-person social capital, which was higher among responders in big cities. It is important to note that some of the quiz questions may have favored people who live in more diverse places, like big cities, such as “There are people who make me interested in things that happen outside my town,” or “I come into contact with new people all the time.”

Perhaps in-person social capital increases in cities due to the sheer number of people in close proximity to each other. It could also be that people who seek a lot of social connection are drawn to live in urban areas with larger populations.

People on the West Coast had higher social capital. People in the northwest of the U.S., in particular, had higher overall social capital scores than any other group. This difference seems to be caused primarily by in-person social capital, which was significantly higher for those responders on the West Coast.

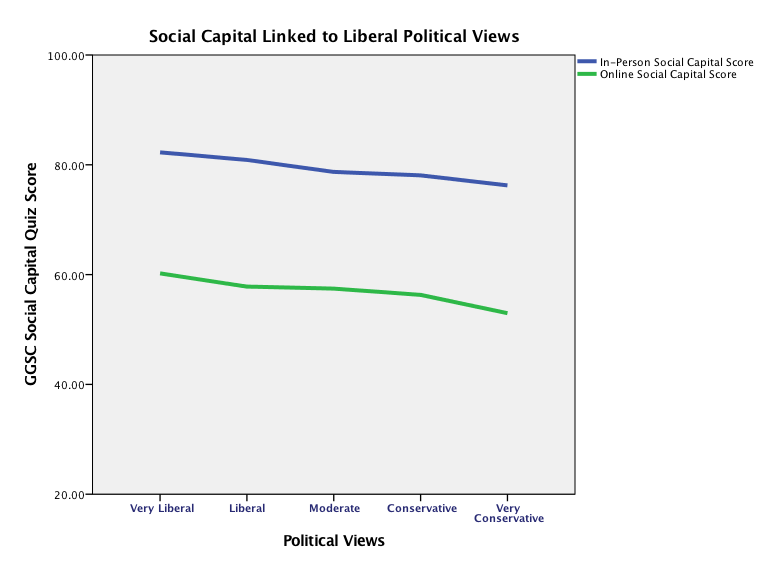

Liberals might have more social capital than conservatives. People who identified themselves as “very liberal” and “liberal” had significantly higher overall social capital scores than people on the more conservative end of the spectrum; people identifying as “very conservative” had significantly lower social capital scores.

This was true for both in-person and online social capital; more liberal people tended to have more connections both face-to-face and on the Internet.

We have a few guesses as to why this pattern exists. It’s important to note that less than two percent of our respondents identified as “very conservative,” which tells us more about Greater Good readers than social capital. Indeed, the language in some of the quiz questions reflects values that are known to be more “liberal,” such as fighting injustice and having a nurturing stance towards diverse people. According to Robb Willer, who studies how to be more empathic to people with different political perspectives, “liberals tend to endorse values like equality, fairness, care, and protection from harm more than conservatives. Conservatives tend to endorse values like loyalty, patriotism, respect for authority, and moral purity more than liberals do.”

In summary, when it comes to in-person social capital, our responders with the highest scores were highly educated and liberal 30-69 year olds in big cities on the West Coast. And those savviest at developing meaningful connections online were liberal 30-49 year olds. Interestingly, there were few differences in online social capital related to geographical location, neighborhood, and education.