How to Find Joy after Adversity

In her new book, Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg recounts her journey of healing after the death of her husband.

Losing a spouse is among the most devastating losses. Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg knows this firsthand. She lost her husband, Dave Goldberg, two years ago when he suffered a traumatic brain injury from a fall during their vacation.

But, with the help of family, colleagues, and friends—including management professor Adam Grant of the Wharton School—she learned how to cope with overwhelming grief and has even made strides toward finding joy again.

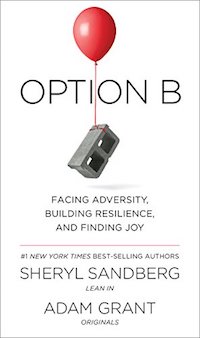

Now, she’s written a book—part memoir and part self-help book—chronicling her journey and sharing what has helped her to cope, called Option B: Facing Adversity, Building Resilience, and Finding Joy. Co-written with Grant, the book provides both an inside look at grief and research-based guidance on how to deal with adversity in a healthier way.

The authors decided to use only Sandberg’s voice in the book, and, as it turns out, it’s a very compelling one—full of honesty, pain, humility, and hope. Her candidness is part of what grounds the book, giving it a gravitas it might not otherwise have. Though Sandberg’s life may seem charmed, it’s clear the loss of her husband shook her world.

After his death, she began to look for inspiration on how people recover from loss. She learned that recovery can be hard if one falls prey to the “3 P’s” associated with depression: “personalization—the belief we are at fault; pervasiveness—the belief that an event will affect all areas of our life; and permanence—the belief that the aftershocks of the event will last forever.”

While these may be common responses to the death of a loved one, studies have shown that we fare better when we avoid them. Sandberg had to work through the fear that she would never find happiness again, and that she could somehow have done more to prevent Goldberg’s death.

How to do this? Sandberg recounts some of the steps she took, including reaching out to loved ones for validation of her feelings and thoughts, for general emotional support, and for hope and inspiration for recovery. She learned about accepting her feelings rather than fighting them, practicing gratitude, and using cognitive-behavioral techniques—like questioning and counteracting irrational thoughts.

“I started to learn that no matter how sad I felt, another break would eventually come,” she writes. “It helped me to regain a sense of control.”

She also drew upon the science of self-compassion—a combination of accepting our suffering, not blaming ourselves, and seeing our struggles as part of the human experience. Research has shown that self-compassion helps people move on from hardship, even hardship they may have inadvertently brought on themselves. Though at first not willing to embrace self-compassion, Sandberg came to see it as an important step in moving forward.

Sheryl Sandberg and her husband, Dave Goldberg.

Sheryl Sandberg and her husband, Dave Goldberg.

“Self-compassion often coexists with remorse. It does not mean shirking responsibility for our past. It’s about making sure that we don’t beat ourselves up so badly that we damage our future,” she writes.

Journaling can also help people recover from difficulty and trauma, as can exercises like “Three Good Things,” where you list positive things that occurred during your day. Though Sandberg found these helpful, Grant encouraged her to move toward writing about little things she’d accomplished. Even recording small steps, like making a cup of tea, helped slowly build her self-confidence, giving her hope that she would function normally again.

One of Sandberg’s key insights is that suffering alone doubles the suffering. While she admits it’s hard to know what to say to someone who is hurting—she recalls some of her own cringe-worthy attempts at expressing compassion—she advises friends and family to acknowledge losses anyway. Not saying anything only makes the person feel more isolated and alone, while showing up, asking questions, and listening lets people know that they can count on you to be there.

She also found solace in the research and stories around post-traumatic growth—or bouncing forward rather than simply bouncing back from trauma. By “finding personal strength, gaining appreciation, forming deeper relationships, discovering more meaning in life, and seeing new possibilities,” people can make sense of their experiences, which helps them to recover, writes Sandberg. For her personally, increased appreciation for relationships she’d taken for granted and increased meaning in her work were particularly helpful.

While dealing with her own grief was difficult enough, Sandberg needed to find ways to help her children, too. Part of that was allowing them to feel their feelings, to frequently recall stories about their father, and to create new rituals and activities they could enjoy together in their new family system—including, embracing new games they could play together and practicing gratitude for the good things in their lives.

Perhaps because of the response to Sandberg’s earlier book, Lean In—which some criticized for not adequately addressing the role of privilege and marital support versus poverty and single parenting in work life—Sandberg was more careful to address the issues of inequality head-on. She admits having the luxury of focusing mostly on the emotional rather than financial pain of losing a spouse, and cites statistics showing just how dire this can be for someone on the edge of poverty.

“I started to learn that no matter how sad I felt, another break would eventually come. It helped me to regain a sense of control.”

Though I’m sure her experience has given her more empathy for single parents, I felt that many of these passages fell a bit flat. While I wholeheartedly agree with her argument that “it’s important to erase the wage gap for all women and especially women of color” in order to help them recover from setbacks, it seemed tacked on to the story of her own personal journey.

Still, overall, I found the book compelling and readable. It’s good to see how Sandberg has been able to hold her grief, but still find some joy in her life—even learning to date again. And, I appreciated the research-based tips on how to recover from trauma. As she knowingly writes, “We all deal with loss: jobs lost, loves lost, lives lost. The question is not whether these things will happen. They will, and we will have to face them.” It’s nice to have a few tools in hand for that time.