Can Social-Emotional Learning Help Disadvantaged Students?

By Meredith Kolodner

New York City's experience with community schools illustrates the possibilities and pitfalls of a new educational model.

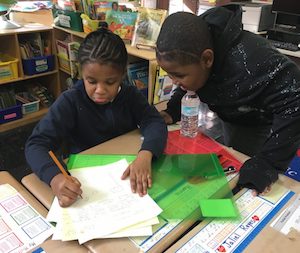

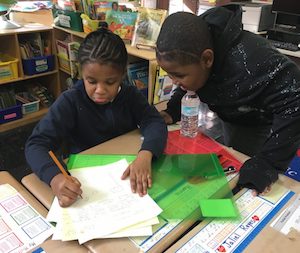

Fourth-graders at P.S. 67 often work in groups. They are asked to write several drafts of essays to get used to revising their work.Tal Bar-Zemer

Fourth-graders at P.S. 67 often work in groups. They are asked to write several drafts of essays to get used to revising their work.Tal Bar-Zemer

Literacy is a major focus at P.S. 154, starting with the youngest students.Meredith Kolodner

Literacy is a major focus at P.S. 154, starting with the youngest students.Meredith Kolodner

Mariah Mayweather, who is in fifth grade at P.S. 67, says she has noticed positive change at her school in the past year.Tal Bar-Zemer

Mariah Mayweather, who is in fifth grade at P.S. 67, says she has noticed positive change at her school in the past year.Tal Bar-Zemer

All students at P.S. 154 begin their day with a morning meeting.Tal Bar-Zemer

All students at P.S. 154 begin their day with a morning meeting.Tal Bar-Zemer

New York City's experience with community schools illustrates the possibilities and pitfalls of a new educational model.

The zone for Public School 67 was drawn exclusively around the sprawling Ingersoll public housing complex, but as children trudge into the building, they can see the tips of the gleaming glass luxury towers that are reshaping the skyline around them in downtown Brooklyn.

No children from those luxury condos have enrolled in P.S. 67. It has roughly 225 students; 99 percent are low-income. The school has struggled to stem sliding enrollment and to address poor safety ratings by parents and test scores that were among the worst in the city.

Fourth-graders at P.S. 67 often work in groups. They are asked to write several drafts of essays to get used to revising their work.Tal Bar-Zemer

Fourth-graders at P.S. 67 often work in groups. They are asked to write several drafts of essays to get used to revising their work.Tal Bar-Zemer

In 2012, city officials became convinced that the school could not improve and began the process of shutting it down.

But community members rallied to keep it open, in part because of its auspicious beginnings—it was the first public school for black students in Brooklyn, opening the same year that slavery ended in New York, 1827—and in part because parents weren’t convinced that a new school would solve old problems.

So in the fall of 2015, P.S. 67 began the year with yet another new principal, this time as part of the city’s “Renewal” program, a last-ditch effort to rescue failing schools. And now the community’s wary acquiescence to yet another effort to “fix” the school has morphed into something more elusive—hope.

Enrollment has stabilized, attendance has improved, and parents say they feel welcome in the building.

“This principal is the best we’ve had in a long time, but it’s more than that,” said John Rondon, who has taught at P.S. 67 for 27 years. “There’s something that’s changed internally. The fear we’re going to be closed down isn’t there as much. Somebody said to us, ‘You’re valuable,’ and the kids feel that.”

Last year, 23 percent of the school’s third-graders passed the state reading test, up from 0 percent in 2014. School staff members, in part, credit the improved academics and optimism to the targeted extra resources that come with being a Renewal school, a sort of supercharged version of a “community school.”

Where the model works, it offers hope for other struggling schools in poor and disadvantaged neighborhoods, not just in New York, but nationally.

The stakes have become extremely high. If the Renewal program succeeds, it could become a prototype for improvement elsewhere. Until recently, education reform has prioritized the growth of charter schools, enforcement of strict discipline, and high-stakes testing. As those ideas have produced less progress than anticipated, community school advocates hope their model can take over the mantle of reform.

Reforming education with community schools

Literacy is a major focus at P.S. 154, starting with the youngest students.Meredith Kolodner

Literacy is a major focus at P.S. 154, starting with the youngest students.Meredith Kolodner

The country has approximately 5,000 community schools, according to the National Center for Community Schools. The model is based on the idea that diagnosing the social and emotional needs of children and their families and then alleviating barriers such as hunger, mental health issues, and poor eyesight will make academic success more attainable. Research has shown that the model can be successful, although, as in New York, progress in some places has been uneven.

“Academic failure doesn’t happen in a vacuum….Students don’t fail by themselves, it’s a whole culture of failure that happens,” said the New York City Schools Chancellor Carmen Fariña, explaining why she mandated that all Renewals had to become community schools. “I wouldn’t have imagined doing this without community schools as a model.”

In New York City, Renewal schools got extra funding—about $547 million over three years for 94 schools—to provide more services, such as an extra hour of instruction for all students and additional mental health services. And each school has been paired with a community group “partner” to help serve various needs.

But some supporters of the community school model worry that the Renewal schools’ rushed and uneven progress in New York may tarnish the whole concept.

“I’m very frustrated…and I’m very fearful of what will happen with this program,” said Michael Mulgrew, president of the United Federation of Teachers and a backer of community schools. “The funding by the city is there; it’s now more about the management system.”

Indeed, out of the original 94 Renewal schools named in 2014, Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration has already closed three and merged five others into non-Renewal schools, arguing that families have “better options” in those communities. Schools were chosen for the Renewal program because they were in the bottom 5 percent of lowest-performing schools in the state, among other unwanted distinctions. On average, in the selected schools, less than 8 percent of children were reading at grade level in 2015; 88 percent of students were black or Latino; and students were also poorer, more likely to have learning disabilities, and less likely to be fluent in English than students at other city schools.

Even by Renewal school standards, the children at P.S. 67 have a very high level of need. According to principal Kyesha Jackson, close to one in five children there are homeless. The school’s neighborhood has the highest rate of gun violence in Brooklyn. Children are dropped off and picked up inside the school’s cafeteria or auditorium, rather than the schoolyard, at parents’ request. Almost 30 percent have some kind of disability.

Jackson was made principal only five days before the start of school in 2015, having never met her community partner, Tal Bar-Zemer, a community school director from the nonprofit group Partnership with Children. By a stroke of rare good luck, their shotgun relationship worked.

Children have noticed the change in the school.

Mariah Mayweather, who is in fifth grade at P.S. 67, says she has noticed positive change at her school in the past year.Tal Bar-Zemer

Mariah Mayweather, who is in fifth grade at P.S. 67, says she has noticed positive change at her school in the past year.Tal Bar-Zemer

“There’s less fighting, better security, and we have more stuff,” said Mariah Mayweather, who is in fifth grade. “It makes you want to come to school more.”

Jackson was new to the community school model, but having spent 16 years teaching in another high-needs Brooklyn school, she found it made sense to her.

“I know we would not have had as much progress without the community school model,” said Jackson. “There were so many issues that just with an [assistant principal] and a guidance counselor, we would not have been able to handle it.”

Jackson said that Bar-Zemer, who focuses on attendance issues and parent involvement, has played an important role in the school’s progress. Her presence and the division of labor mean that Jackson can concentrate on the academic and instructional issues. She visits every classroom every day, which allows her to get to know the kids and give the teachers immediate feedback.

“We try to help decrease the stresses and remove the barriers to learning,” said Bar-Zemer. “In high-needs schools, teachers are the first line of defense; you’ll see them bringing in coats and food, trying to find legal help for families. We take the onus off of them so they can teach.”

As to the infusion of funding and services, Bar-Zemer said, “Equity isn’t equality. Some kids and schools need more stuff, because they have less stuff.”

Partnership with Children also provides a full-time social worker and two part-time interns. They help connect families that have legal, housing, or medical issues to resources, and they run courses in each classroom on topics like how to deal with strong emotions. They also see 14 children weekly in individual counseling and 24 in groups where they use art or other activities to work through difficult issues and trauma.

The counseling “is as important as the academic piece. We have been able to develop a culture where they learn that there are people here to support them,” said Jackson. “They can reach out through words and art rather than belittling others and lashing out. And they are expected to do so.”

Bar-Zemer said a “student sorter” program given to all the Renewal schools has also been very useful. She can filter student attendance by commute time, past attendance, counseling status, and class. One pattern they found was that attendance is higher across the board on the days the school has its art program.

“It allows us to look at problems and also celebrate successes,” said Jackson.

Why some Renewal schools flounder

But not all the Renewal schools have made the same progress as P.S. 67.

By the program’s own measurements, a number of schools have not succeeded. More than one-third of the schools haven’t met even half of their own goals for attendance, academic progress, and other improvements. Among its 31 high schools, graduation rates increased in 21 and decreased in eight over 2015 (two stayed the same).

Community school advocates blame the failures on the rollout and management, not the program itself. To begin with, not all the principals in the schools dubbed Renewal were convinced of the community school model. Some new principals had no idea what a community school was. And not all of the superintendents who did the hiring fully understood what was required in a community school.

In addition, because the 86 current Renewal schools are spread among 27 different superintendents, the average superintendent has just two or three Renewal schools among the roughly 50 he or she oversees.

And the rollout has been undeniably messy. For example, it wasn’t until this past August, more than a year after the program began, that the city held its first meeting between principals and community school directors to discuss the most effective ways to build a community school.

That lack of coordination has played out at the school level, too. At one school in the Bronx, for example, the community partner and the principal didn’t meet until the first day of school last year. The crush of the first weeks of school and the tensions that ensued meant that community staffers were not in place to lead the extra hour of learning time until November. And no mental health services were available in the school until January.

At the citywide level, the Education Department’s separate silos for the superintendents and the Office of Renewal Schools have also had an impact. Some principals say they have received missives from superintendents that conflicted—or weren’t coordinated—with directives from the Office of Renewal Schools.

Early last fall, for example, each Renewal school received word that they should hold a “state of the school” event in late September and invite parents, community members, and elected officials. But each school was also told, by a different office, that they must hold a family night in September as a way to build family and community involvement. School leaders, completely overwhelmed, protested, and eventually the two events were combined.

Fariña acknowledges that there have unanticipated problems. “With any new programs, there are going to be bumps in the road,” she said.

“From the very beginning we focused on writing and literacy in particular,” said Fariña, who was a teacher for 22 years. “If I had to change one thing right now, I would say I wish we had done the same thing with math.”

“One of the changes we made is clearer lines of hierarchy,” she added, “because superintendents really own these schools now, which they didn’t in the beginning. I think the schools not making as much of a success are the ones where part of the structure fell apart.”

In addition to the coordination issues, educators and some community groups say there has not been enough systematic attention paid to improving instruction. Parent and community groups such as the Coalition for Educational Justice fought to get expert teachers into the schools, but the agreement came too late to recruit enough teachers for all the schools in the program’s first year.

This year, however, there are 241 model teachers in the schools, which several principals say has helped enormously—especially since teacher turnover is high in challenging schools.

School experts had expected higher turnover in the Renewal schools as teachers who were a poor fit cycled out. But at some schools, it wasn’t the long-term teachers who left. At a dozen of the Renewal schools, at least half of the teachers newly hired in 2015-16 didn’t come back this past fall.

City officials say that getting the right leadership in place has been the most important step to getting the schools on the road to improvement. Indeed, close to half of the original principals have been replaced.

Officials are also working to give more guidance about the use of the extra hour of learning time. “We’ve learned that working with individual communities to implement it works better” than simply providing the extra hour without much guidance, said Aimee Horowitz, executive superintendent of the Office of Renewal Schools.

But advocates’ biggest fears center on whether the progress that has been made will be recognized so that the program can continue.

“The timeline for academic turnaround and attendance improvement is very short,” said Robin Veenstra-VanderWeele, the chief strategy officer at Partnership with Children. “In the court of public opinion, a few points increase in attendance and reading scores is going to look incremental, and since it is hard to create other standardized measurements, we’re not measuring anything else.”

All students at P.S. 154 begin their day with a morning meeting.Tal Bar-Zemer

All students at P.S. 154 begin their day with a morning meeting.Tal Bar-Zemer

P.S. 154 in the South Bronx is another Renewal school that struggled for years, was almost closed, and is now improving. Alison Coviello taught there for 12 years before becoming principal in 2012. That year, on the annual schools survey, only 13 percent of teachers said that order and discipline were maintained.

Coviello’s first move was to try to change the school’s culture by instituting some new morning procedures. They began using a single entry point and walking children to their classrooms, so they at least knew who was in the building.

That was only the beginning. Coviello also instituted morning meetings and designated that a staff member be on call at all times if a classroom teacher felt they couldn’t handle a disruption. Things didn’t change overnight, but four years later children no longer run through the halls, adults no longer scream at students, and children are engaged in classrooms. Last year 27 percent of children passed the state English exam, up from 5 percent in 2013.

“We wouldn’t be able to go into the academic work without these other things in place,” Coviello said.

The school now has a full-time asthma manager, through the Renewal program, who has helped improve family health and school attendance. She not only treats patients, she goes into homes to assess risk factors. Like some other Renewal schools, P.S. 154 found that asthma was a big reason for absences, as children were kept home when they were sick or when their parents were too ill to take them to school.

And then there are housing issues. The heat and hot water went out during the coldest weekend in January at the Mitchel Houses, where the majority of the children live. Attendance plummeted that Monday as children who were unable to bathe, get clean clothes, or sleep properly stayed home.

P.S. 154’s community partner, the YMCA, provides nine staff members, who work as teaching assistants in every kindergarten, first- and second-grade classroom.

Like Jackson, Coviello said the school couldn’t have improved as much as it has without the community school services. And like other teachers and principals at several Renewal schools, Coviello and her team say that it was the belief that they could improve that made the key difference.

“It was the first time at this school that anyone came with the lens of ‘What’s going well and how can we support it?’ instead of looking for what’s wrong,” said Coviello. “The paradigm of support instead of shutting down—it’s huge. I can’t even put into words what it did for us and our morale.”

This story was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Read more about Race and Equity.