What Would Buddha Do About the Economy?

By Jenara Nerenberg

Clair Brown suggests that the moment may be ripe for Buddhist thought to insert itself into Western economics.

Clair Brown

Clair Brown

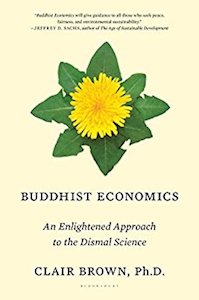

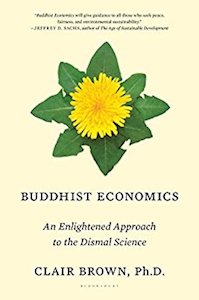

Buddhist Economics: An Enlightened Approach to the Dismal Science (Bloomsbury Press, 2017, 218 pages)

Buddhist Economics: An Enlightened Approach to the Dismal Science (Bloomsbury Press, 2017, 218 pages)

Clair Brown suggests that the moment may be ripe for Buddhist thought to insert itself into Western economics.

The financial collapse of 2008, coupled with growing income and wealth disparity, has made many Americans question the benefits of a free market economy. Are our current economic policies really the best we can do?

According to Clair Brown, a UC Berkeley economics professor and director of the Center for Work, Technology, and Society, the answer is no. An expert in economic theory and a practicing Buddhist, Brown believes we should consider integrating a Buddhist value system into economics, arguing that if we focused more on relieving suffering, on our interdependence with each other and nature, and on sustainability, our economy would work better for more people. Her thinking is explored in a newly published book, Buddhist Economics.

I talked with Brown about the promise and potential of Buddhist economics, what went wrong in our current economic framework, and how it all connects to individual well-being.

Jenara Nerenberg: How do you define “Buddhist economics”?

Clair Brown

Clair Brown

Clair Brown: Buddhist economics is based upon three main assumptions: People are interdependent with each other, people are interdependent with nature, and happiness requires helping others and reducing suffering, because the suffering of one person is the suffering of all people.

JN: What prompted you to write a book on this topic?

CB: Students care a lot about inequality and sustainability, but somehow both are discussed outside of economics, as though it’s separate. But that’s not satisfying. Students want something that’s much more integrated and holistic.

Economists have worked a lot on these problems, but once again by the time we’ve worked on a problem and beat it to death, it’s still separate. So we know a lot about inequality and sustainability. We also know all the reasons that free markets don’t work and that the assumptions don’t hold. But it’s very hard to find a way to integrate it all.

So for me, as a practicing Tibetan Buddhist, I thought, “How would the Buddha teach introductory economics? How would he bring it all together?” And my students loved it and really helped push my thinking along.

JN: What is some of the most compelling research you came across when working on the book?

CB: I started off with Amartya Sen, the Nobel Prize winner, whose work looks at how people are living to evaluate their quality of life. When Amartya Sen read my book, he thanked me for pushing along what he’d been doing, especially because sustainability wasn’t a big part of his work at the time. Ecological economics is the reason why I say humans are interdependent with nature. Our well-being is interdependent. And in looking at human suffering, I turned to the United Nations—they were working on sustainable development and basic needs, relieving suffering of extreme starvation and extreme poverty.

Then there’s the fascinating topic of how economists disagree over what is human nature. The competitive market model assumes we are selfish, as Adam Smith shows. But new research shows just how altruistic people actually are and so economists finally have proof and can no longer say that humans are just selfish. And that was a big breakthrough. Of course only economists need such proof!

JN: How has economics contributed to our current political climate and what can be done about it?

Buddhist Economics: An Enlightened Approach to the Dismal Science (Bloomsbury Press, 2017, 218 pages)

Buddhist Economics: An Enlightened Approach to the Dismal Science (Bloomsbury Press, 2017, 218 pages)

CB: You know, a lot of economists who studied inequality predicted that the enormous rise in inequality would eventually lead to social unrest. We’ve had a rise in inequality since the ‘70s and it’s gotten worse and worse. It’s well-documented. So we see how bad the inequality is—not just in income, but in wealth.

I look at the people in the cities that have been devastated in the Rust Belt of the South, and I have enormous empathy for them because they have suffered. They don’t have jobs and don’t have the ability to feel good about taking care of themselves and their families. And they’re suffering enormously, because their way of life as they’ve known it—their religion and community life—sort of died for them, and it was a large part of our inequality. So the sad thing is that they—without having enough background in history, politics, and economics—were taken in by someone like Trump who blamed current conditions on trade and immigrants, which economists know is incorrect.

Integrating sustainability into relieving suffering fits really well. Once we’re ready to let go of the idea that people are only selfish, and once we’re willing to assume interdependence among people and nature, then everything works. It all comes together and it’s also compatible with what neuroscientists are finding about people’s well-being and the way minds work.

JN: Which neuroscience research has caught your attention?

CB: Research shows that when people are shown images of people helping others, the happiness centers in their brain light up. And when the images show people behaving selfish and mean, then their brain activity moves away from it. Once again we are verifying that people are actually naturally generous and kind and that somehow society comes and puts a cloud over our Buddha nature of loving-kindness. Society tells you to go make a deal, a lot of money, be competitive, gain power…but that’s not how you become happy. But if society tells you that’s how you become happy, then we’re in a dilemma. And that’s causing us pain.

JN: Do you have other thoughts on economics and well-being?

CB: You know, the relationship between the individual and the larger economic structure is really important. What we say in Buddhist Economics is that individuals should do the best they can—live mindfully, take care of people, have a low carbon footprint, and so forth. But the other thing that they absolutely have to do is get up, go out, and when there’s an injustice being done—as today there is with immigration and the United States withdrawing from the Paris agreements—they have to go out and protest that.

We must stop injustice against people and we must stop harm to the earth. We can’t just sit at home and feel good about how nice our life is, because we live in the greater world. And right now we absolutely have to go out and push our government to behave in a way that protects people and doesn’t harm them and protects earth and doesn’t harm it.